I see each visit to Brno and every invitation to conduct the Brno Philharmonic as a return to the land of my conducting youth. The State Philharmonic Orchestra in Brno was my first major position after graduating from the Academy and not only did I learn a great deal professionally there, but I also started a large number of friendships many of which have lasted until today. That is something I appreciate probably the most.

Jiří Bělohlávek conducted the State Philharmonic Orchestra Brno for the first time at a New Year’s Concert on 1 January 1972. The collaboration was successful and so many more activities followed. The first was a studio recording of Aram Khachaturian’s suites. Bělohlávek’s debut recording and LP debut at the same time caught the attention of the press, where Jiří’s impressions of the recording process were published. In 1973, the Philharmonic received an award for the 1972 best recordings of the Supraphon label.

It is a different feeling, a different kind of work in the studio and a concert hall. At a concert, after a number of rehearsals where you “knead the work to your image,” you feel the audience’s reaction directly, whether it is positive, reserved or even negative. One lacks this spontaneous immediacy in the studio and the performer must try to accept the role of an objective listener while listening to the recorded track. It is very difficult.

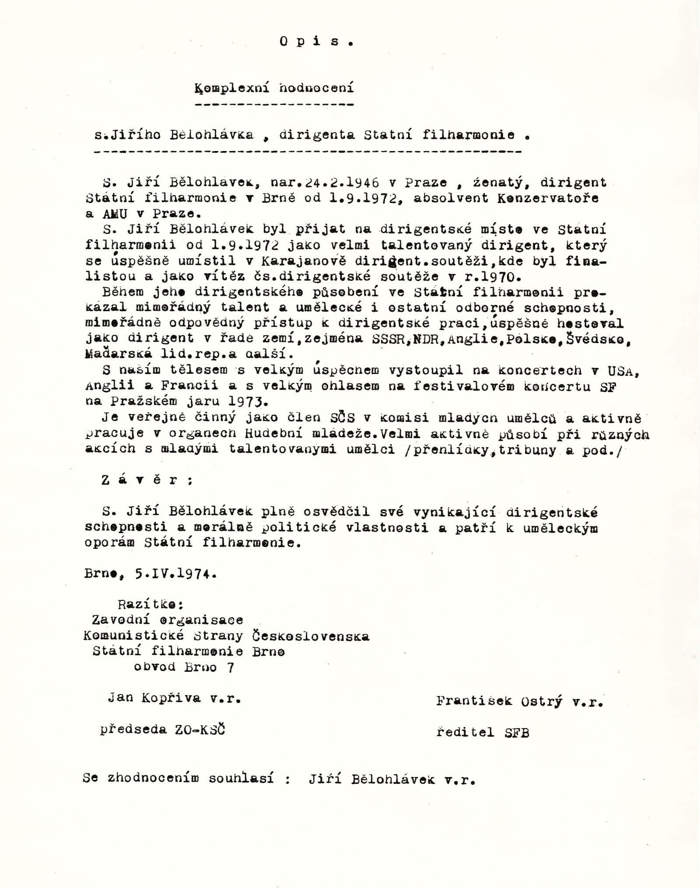

The collaboration developed even more significantly after the orchestra’s offer of the position of its second conductor, starting in September 1972. Bělohlávek accepted the position and moved to Brno after his graduation from AMU. Since the early 1960s, Jiří Waldhans had been the orchestra’s chief conductor, and a very successful one as he had managed to build and develop the fundamental classical repertoire, introduce thematic subscription concerts – both chamber and symphonic - into its concert programme and took the orchestra abroad more often. However, due to advancing illness, Waldhans could not conduct all of the orchestra’s concerts himself. Engaging a young energetic conductor capable of performing demanding tasks was a good solution to a difficult situation.

Bělohlávek’s first professional position turned out to be an intensive practical school for him, not only in the field of music, but also in management. How to work efficiently and on a long-term basis with an orchestra composed of various individuals? How to convince the players to support him and how to make them enthusiastic about his conception of the music? How to deal with conflicts or – better still – prevent them? Solving these and other tasks became an important part of Bělohlávek’s further professional growth.

I came there as a total greenhorn and I found a so-called C-team on the one hand, which consisted of young violinists and string players sitting in the back. I established an enormously lively contact with them right away. I supported their team and they supported me. (…) And on the other hand, I had to face first resistance – they called me names referring to my Czech (as opposed to Moravian) origin and thinking: Who is he to tell us what to do? There was a clarinet player who did his best to give me a hard time. He never missed an opportunity to test me, playing something else than he should and then observing if I was going to react. Luckily, I responded most of the time, I think, and after two years he became almost a fan of mine.

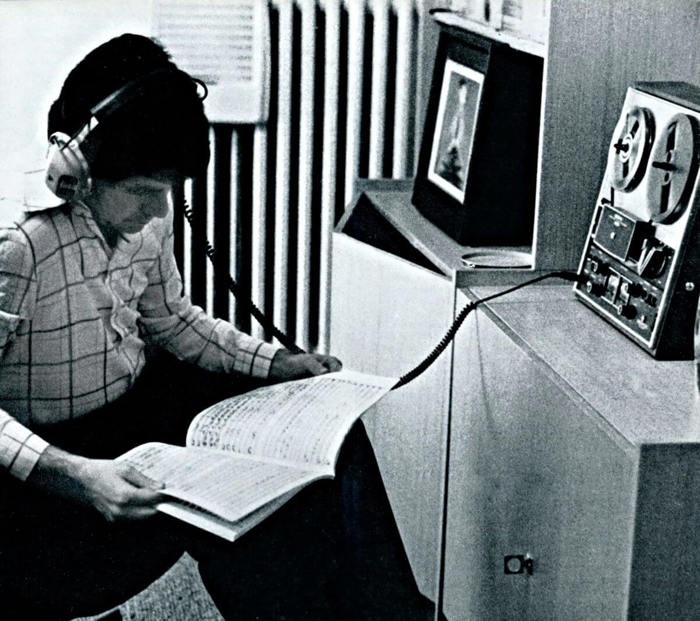

Despite some dissonance, Bělohlávek recalled Brno as an idyll where he had plenty of time both for preparation and for his hobbies. He would, for instance, go to Janáček’s Museum to study the composer’s manuscripts or he would analyse rehearsal recordings with similarly enthusiastic orchestra members.

I used to be crazy about the tape recorder. I got my first magnetophone, and I recorded all the rehearsals. We then sat the whole afternoon with the most passionate of the orchestra players, listened to the recording and made conclusions about what had to be improved… It was fantastic!

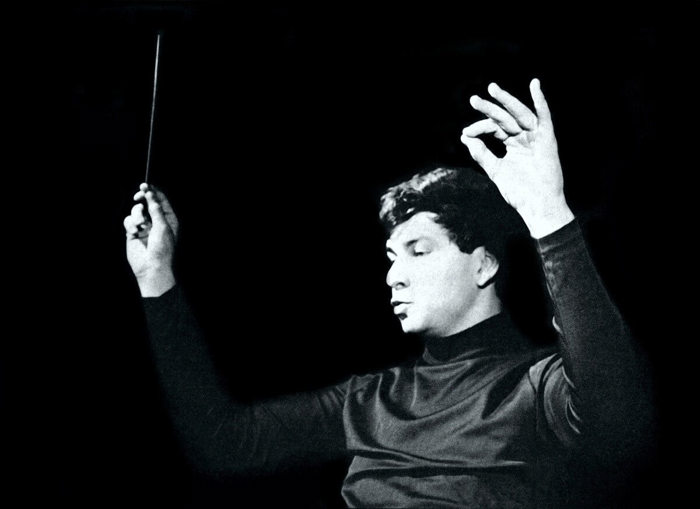

Jiří Bělohlávek’s first performance in the role of the orchestra’s new permanent conductor took place at one of the subscription concerts on 19 and 20 October 1972 and his debut drew a lot of attention. He conducted Béla Bartók’s Concerto for Piano and Orchestra no. 3 with the Italian pianist Gloria Lanni, Alfredo Casella’s Serenata and Johannes Brahms’ Fourth Symphony.

The orchestra, the audience and the critics have been wondering if Bělohlávek was capable of further consolidation and dynamization of the orchestra’s endeavours. (…) It seems that this young conductor is fanatical about his work, tireless when it comes to rehearsing and a worshipper of detail (…) A certain atomisation may have occurred, but the road to perfection leads more likely through the overemphasis of details which when gradually put together create the overall clear conception rather than through the immediate understating of the whole while lacking the fundamentals. We cannot be sure of the answers to the initial questions yet, we will have to wait for more performances by this young conductor. It is, however, already clear that he introduced the right working procedure and only time will tell if he can persevere, for both his and the orchestra’s benefit.

Bělohlávek’s first season with the orchestra was full of events significant for the orchestra’s history. Early in 1973, the Philharmonic together with its two conductors and soloists – including the violinist Václav Hudeček – went on a tour to the USA for the first time ever. Named for publicity reasons the Czech State Orchestra Brno, it performed eighteen concerts in seventeen cities in twelve states between 31 January and 23 February. [ 6 ]

Two nights at the legendary Carnegie Hall framed the tour. The opening concert on Seventh Avenue was conducted by Jiří Bělohlávek.

Listen to the recording of the 2nd suite of Daphnis & Chloé by Maurice Ravel, performed by the Czech State Orchestra under the baton of Jiří Bělohlávek during their first American tour in Tifton, Georgia, on Sunday, February 18, 1973.

Despite the busy programme in which the orchestra travelled more than fourteen thousand kilometres, they found the time to go to a concert of the world-famous New York Philharmonic conducted by the world-famous Leonard Bernstein. Jiří Margolius remembers this unforgettable night beautifully in his text from the tour:

And New York again … Our tour is at its end. One more concert at the Carnegie Hall and then home. Václav Hudeček has two days off, he played his last concert in Harrisonburg, Virginia. That’s why he’s going to see the New York Philharmonic conducted by Leonard Bernstein. The orchestra’s playing is excellent and the delight from the conductor’s performance is unforgettable. During intermission, Václav Hudeček and Jiří Bělohlávek are going backstage, as the famous conductor wants to meet them. Václav gives Bernstein his new LP with Dvořák and does not forget to speak about the success Bernstein’s TV Young People’s Concerts had in Czechoslovakia. “Well Prague, that’s a city of music” the conductor says. On the way back to the hotel, the young musicians buy a newspaper with reviews of the last concert of the Brno Philharmonic in Macon which speak about Mr. Jiří Bělohlávek having everything that Leonard Bernstein had when he was twenty-seven years old, an age which the Czech conductor reached that very evening.

…the program was most warmly received, and rated a standing ovation at eveningʾs end (initiated by some who are usually the last to rise.) One standout reason for this response was the masterful conducting of Jiri Belohlavek, whom inquiry revealed to be but 26-years-old, the Czech equivalent of a Young Leonard Bernstein, we suspect.

The orchestra worked to various effects in a program that included Dvorak's ‚Carnival‘ Overture and Violin Concerto and Ravel's Suite No. 2 from ‚Daphnis and Chloe‘. The conductor was 26‐year‐old Jiří Bělohlávek, looking younger than his players, and he seemed to function in relation to the repertory as do young conductors from any country. Leading everything from memory, Mr. Bělohlávek, treated the romanticism of Dvořák with efficiency rather than warmth. He seemed much more interested in the Ravel work, sometimes drawing out phrase lines more than is customary. It wasn't until the encore, the exuberant Slavonic Dance No. 15 of Dvorak, that everything came together in a wonderfully rhythmic and rousing performance.

In the first half of 1973, another significant moment was on the schedule – two concerts of the Brno Philharmonic at the Prague Spring Festival on 24 and 25 May. The first concert was conducted by the Hungarian conductor György Lehel. The second one was conducted by Jiří Bělohlávek – the programme at the Smetana Hall consisted of four compositions, including Beethoven’s Piano Concerto no. 3 in c minor and Martinů’s La Bagarre. It was Bělohlávek’s symphonic debut at the festival, while his very debut at the festival took place a year earlier when he conducted the Prague Chamber Orchestra in St. Vitus Cathedral.

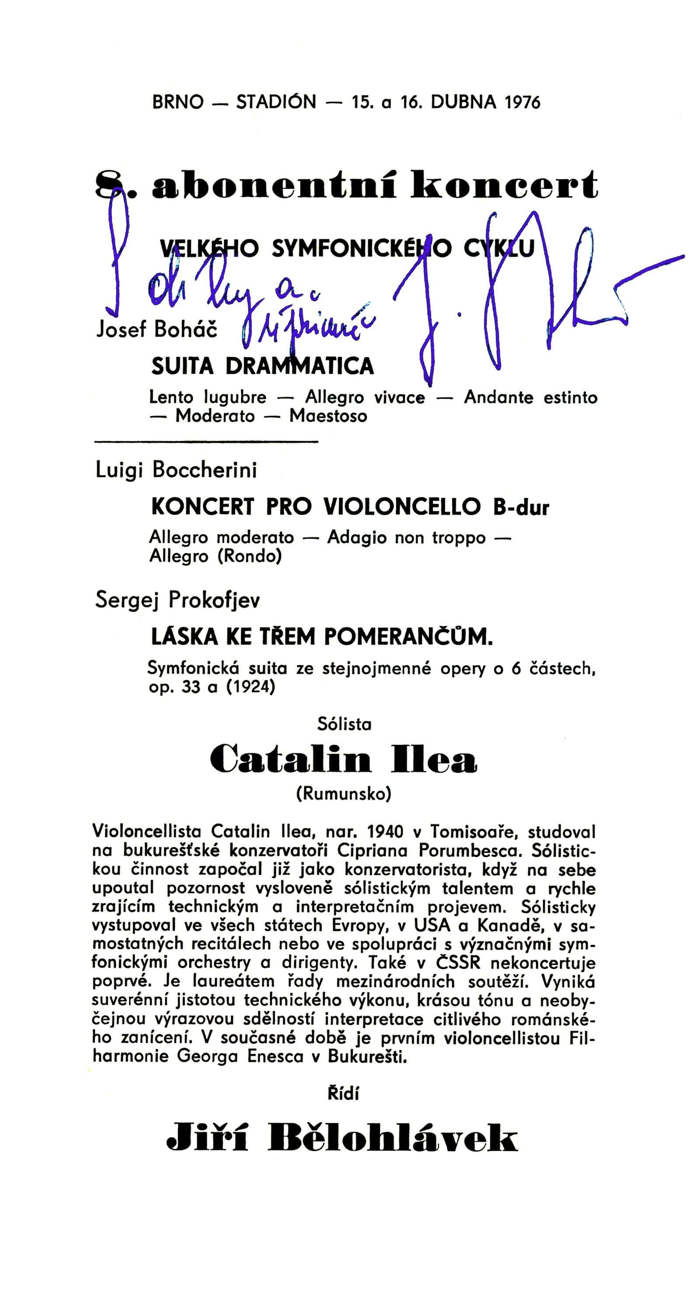

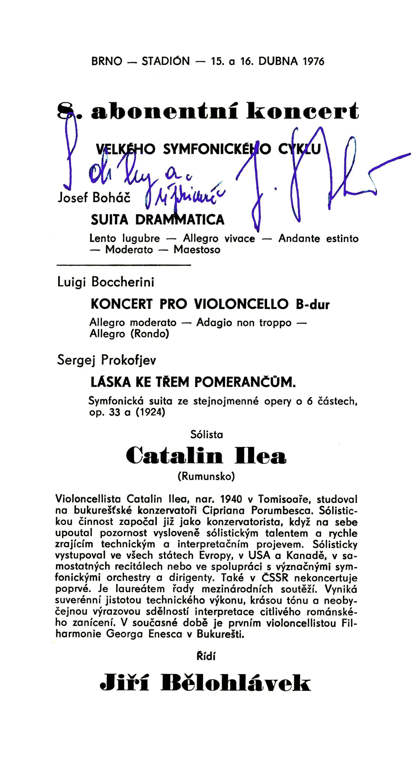

In the following seasons, Bělohlávek conducted a range of subscription concerts from the World Symphony Cycle, Large Symphonic Cycle or Sunday Concert Matinees. Already in Brno, he focused on one of “his authors” – Gustav Mahler. [ 10 ]

He aimed at contrasting and precisely crafted planes in which every fully resounding detail was subordinated to a purposefully constructed and firmly unified whole in a magnificent and musically singing Mahlerian fresco of strongly dynamic and dramatic effect.

In March 1975, Bělohlávek and the Brno Philharmonic performed Mahler’s First Symphony in D major, “Titan”, and Symphony no. 4 G major about two years later. In December 1977 he conducted Mahler’s Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen and Rückert Lieder. He would develop his path of Mahlerian interpretation further with the Prague Symphonic Orchestra.

Bělohlávek made with the Brno Philharmonic a number of successful tours abroad and was becoming more and more known in music institutions, agencies and promoters outside of the country. Following the US tour, they played in the UK, both West and East Germany and Austria. [ 12 ]

Within Czechoslovakia, Bělohlávek conducted a number of important concerts outside of Brno – he performed at the Prague Spring Festival and at the Young Smetana’s Litomyšl Festival, where in September 1977 he conducted Smetana’s Má vlast with the Brno Philharmonic. In Brno, he also made several interesting recordings for radio and recording companies. In addition to Khachaturian’s Masquerade and Gayaneh suites, he recorded, among others, Janáček’s Sinfonietta and Taras Bulba (released 1978 on LP), Liszt’s Piano Concertos no. 1 and 2 with Valentina Kameníková at the piano (released 1977 on LP) and Zdeněk Fibich’s Symphony no. 3 (1983, LP).

It was a fantastic experience back in 1977 for participants of the Young Smetana’s Litomyšl festival. In the chateau riding hall, the Brno Philharmonic performed Smetana’s “Má vlast” (My fatherland). (…) Gone was the official pretence of festival concerts where encores are out of the question. The young audience cheered and the symphonic poem “Šárka” was played as encore! (…) I have never witnessed a more spontaneous reception of the work than in Litomyšl then. It was obvious that Jiří Bělohlávek was a promising Czech master of the baton.

Bělohlávek’s six-year long position as a conductor of the Brno State Philharmonic was successful for both parties. Bělohlávek gained the opportunity to work on a long-term basis with an orchestra of quality, to improve the orchestra’s technical and musical skills and to develop and grow as a conductor. [ 14 ]

And the orchestra could make good use of a young, enthusiastic and hard-working conductor. Even the critics noticed this win-win situation. Václav Holzknecht wrote about it in a review of a concert at the Bratislava Music Festival in October 1976:

The Brno Philharmonic defended their reputation very well among other national and international ensembles. They were very lucky to get a young conductor at the start of his career, a gifted and ambitious J. Bělohlávek, who was also lucky in coming to an orchestra of such quality at this early stage, for both can fruitfully influence each other and develop in this mutual relationship under the best conditions.

During his time in Brno, Bělohlávek also continued his career at the Czech Philharmonic. Since 1973, he had been the permanent guest conductor, performing regularly at subscription concerts at the Rudolfinum and taking part in tours both within Czechoslovakia and abroad. Thanks to his frequent collaboration with the ensemble, a musically fruitful relationship developed.

And the third, but not the least, father of the evening’s success was the conductor Jiří Bělohlávek and the Czech Philharmonic with which he has an understanding like almost no other. The optimal interpretation of Kalabis’s symphony was also the conductor’s contribution; he understood and performed his role in Liszt perfectly and in the concluding work, Beethoven’s “Eroica,” he proved his maturity for the ultimate tasks as well. … This conductor’s lucky star is formed equally by his extraordinary musical talent, diligence, intelligence, and, maybe most importantly, by the magnetic force of a natural sovereign of the orchestra.

Bělohlávek also had a number of opportunities abroad in the first half of the 1970s. In 1974, in the Year of Czech Music, Bělohlávek travelled for the first time to the country of the rising sun and conducted the Japan Philharmonic Orchestra in Tokyo. Japan soon became one of his favourite musical destinations and he toured it in the coming years and decades many times. At this time, he also had his debut in West and East Germany, in Poland, Belgium, Sweden and Finland.

During his Brno period, a personal event of utmost importance happened - Jiří became the father of his daughter Zuzana in 1977.

Main sources

- 1.

BENEŠ, Jiří; BALÁČOVÁ, Jana: Státní filharmonie Brno 1956–2006. Brno: Státní filharmonie Brno 2005, s. 34.

- 2.

(kl): Poprvé na desku. Supraphonrevue 8, 1972, č. 4, s. 3.

- 3.

VEBER, Petr; STEHLÍK, Lukáš: Jiří Bělohlávek: Fluidum, nebo práce? Harmonie 2016, č. 2, s. 6–15. Dostupné online

- 4.

Poslední natočený koncert Jiřího Bělohlávka. V podání Magdaleny Kožené zazněly Biblické písně Antonína Dvořáka. Český rozhlas, 4. srpen 2017. Dostupné online

- 5.

FUKAČ, Jiří: Brněnští filharmonici s mladým dirigentem. Hudební rozhledy 25, 1972, č. 12, s. 544.

- 6.

Author unknown: O koncertním turné brněnské Státní filharmonie po USA. Hudební rozhledy 1973, č. 4, s. 162.

- 7.

MARGOLIUS, Jiří: Čtyři struny. Praha: Magnet 1973, s. 96, 113.

- 8.

McNAIR, Jacqueline: Czech Orchestra Closes Age Gap. Macon Telegraph 147, 1973, č. 49 (18. 2.), s. 7A.

- 9.

ERICSON, Raymond: Czech Orchestra Has Mellow Sound. The New York Times 1973 (2. 2.), s. 16.

- 10.

STRNKOVÁ, Zuzana: Provedení symfonického díla Gustava Mahlera ve Státní filharmonii Brno. Bakalářská diplomová práce. FF MUNI Brno: Brno 2011. Available online

- 11.

VÍT, Petr: Bělohlávkův Tomášek a Mahler. Hudební rozhledy 16, 1975, s. 256.

- 12.

BENEŠ, Jiří: Státní filharmonie Brno 1956–2006. Brno: Státní filharmonie Brno 2005.

- 13.

VÍTEK, Bohuslav: Jiří Bělohlávek šedesátníkem. Harmonie 14, 2006, č. 2, s. 13.

- 14.

TISOŇOVÁ, Lucie: Filharmonie Brno (Státní filharmonie Brno). Dějiny instituce 1956–1989. Magisterská diplomová práce. Filozofická fakulta Masarykovy univerzity v Brně: Brno 2014. Available online

- 15.

HOLZKNECHT, Václav: Bratislavské hudební slavnosti. Hudební rozhledy 1976, č. 1, s. 18.

- 16.

JIRKO, Ivan: Vzrušující filharmonický večer. Hudební rozhledy 1973, č. 2, s. 51.

BENEŠ, Jiří; BALÁČOVÁ, Jana: Státní filharmonie Brno 1956–2006. Brno: Státní filharmonie Brno 2005, s. 34.

(kl): Poprvé na desku. Supraphonrevue 8, 1972, č. 4, s. 3.

VEBER, Petr; STEHLÍK, Lukáš: Jiří Bělohlávek: Fluidum, nebo práce? Harmonie 2016, č. 2, s. 6–15. Dostupné online

Poslední natočený koncert Jiřího Bělohlávka. V podání Magdaleny Kožené zazněly Biblické písně Antonína Dvořáka. Český rozhlas, 4. srpen 2017. Dostupné online

FUKAČ, Jiří: Brněnští filharmonici s mladým dirigentem. Hudební rozhledy 25, 1972, č. 12, s. 544.

Author unknown: O koncertním turné brněnské Státní filharmonie po USA. Hudební rozhledy 1973, č. 4, s. 162.

MARGOLIUS, Jiří: Čtyři struny. Praha: Magnet 1973, s. 96, 113.

McNAIR, Jacqueline: Czech Orchestra Closes Age Gap. Macon Telegraph 147, 1973, č. 49 (18. 2.), s. 7A.

ERICSON, Raymond: Czech Orchestra Has Mellow Sound. The New York Times 1973 (2. 2.), s. 16.

STRNKOVÁ, Zuzana: Provedení symfonického díla Gustava Mahlera ve Státní filharmonii Brno. Bakalářská diplomová práce. FF MUNI Brno: Brno 2011. Available online

VÍT, Petr: Bělohlávkův Tomášek a Mahler. Hudební rozhledy 16, 1975, s. 256.

BENEŠ, Jiří: Státní filharmonie Brno 1956–2006. Brno: Státní filharmonie Brno 2005.

VÍTEK, Bohuslav: Jiří Bělohlávek šedesátníkem. Harmonie 14, 2006, č. 2, s. 13.

TISOŇOVÁ, Lucie: Filharmonie Brno (Státní filharmonie Brno). Dějiny instituce 1956–1989. Magisterská diplomová práce. Filozofická fakulta Masarykovy univerzity v Brně: Brno 2014. Available online

HOLZKNECHT, Václav: Bratislavské hudební slavnosti. Hudební rozhledy 1976, č. 1, s. 18.

JIRKO, Ivan: Vzrušující filharmonický večer. Hudební rozhledy 1973, č. 2, s. 51.