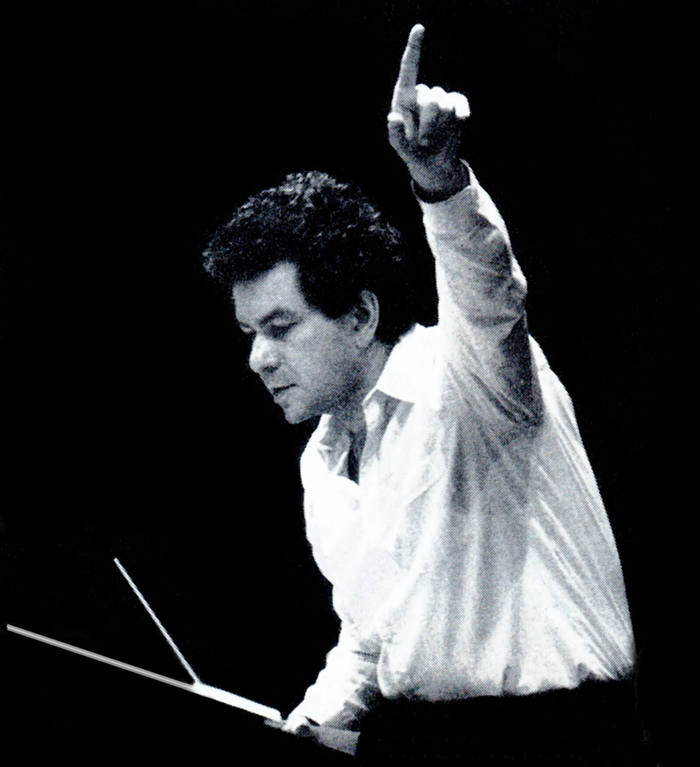

“I started to work as Václav Neumann’s assistant back in 1973 and in 1981 I got a conductor’s position with the Czech Philharmonic, which means that in 1990 when I became the orchestra’s chief conductor, it was a smooth shift for me … but although I took over the orchestra having had thirteen years of experience with the Prague Symphony Orchestra, I was still at the beginning of my career. I jumped right in, headlong.”

The spring months of 1990 were marked by some musical events of utmost significance in Czechoslovakia. One such was the return of Rafael Kubelík who conducted Má vlast at the Prague Spring Festival on 12 May and on 9 June at the Old Town Square in an outdoor Concert of Mutual Understanding. The pianist Rudolf Firkušný came back to Prague after forty-four years and his performance with the Czech Philharmonic and Jiří Bělohlávek at the Prague Spring Festival was commented on in the whole world. For his premiere performance on 28 May 1990 in the Smetana Hall at the Municipal House, Firkušný chose Dvořák’s Symphonic Variations and a composition by Martinů which was dedicated to him by the author and in whose creation he was himself involved. He explained the reasons behind this choice in an interview for Lidové noviny.

I didn’t want to play a solo recital at the festival. I’d known that it would be for me so emotional that I could not be sure that I could play well. For me, it was impossible to imagine in advance what would be going on inside me after so many years when performing on a stage in my beloved Prague, in front of my own audience. I decided to play the “Second Concerto” by Bohuslav Martinů, my close friend for many years. In this way, Jiří Bělohlávek, the Czech Philharmonic and I commemorated the 100 years from the birth of Martinů who sadly could not return home so beautifully as Rafael Kubelík and I could. So at least in this way he was with me.

A live recording of this performance of Firkušný’s was published the following year on a Supraphon album called Rudolf Firkušný in Prague. Firkušný returned to the Czech Philharmonic as soon as December 1990 to make a studio recording of Dvořák’s Piano Concerto in g minor and Janáček’s Concertino and Capriccio for the Sony label, both pieces under Václav Neumann’s baton.

The Concert of Mutual Understanding on 9 June 1990 - Thousands of people gathered at the Old Town Square to hear Smetana’s Má vlast conducted by the legendary Rafael Kubelík and performed by three orchestras – the Czech Philharmonic, the Slovak Philharmonic and the State Philharmonic Orchestra Brno.

On 1 October 1990, Bělohlávek was appointed the chief conductor of the Czech Philharmonic. “According to the new statutes approved by the Ministry of Culture, it was decided by the overall majority of the orchestra members who voted for Bělohlávek unequivocally.” [ 3 ]At the time, they’d already had a twenty-year long period of intensive collaboration as the first time Jiří had conducted the orchestra was already in 1970 as a twenty-four year old; he became a guest conductor in 1973 and a permanent conductor in 1981. As expected, Bělohlávek took over the chief conductor’s role smoothly from Václav Neumann. Still before, he’d made many recordings with the orchestra for two Czech labels – Supraphon and Panton. Bělohlávek’s recording debut with the Czech Philharmonic was an LP entitled Ravel / Bartók recorded in the Dvořák Hall of the Rudolfinum in 1973 and released in 1975. Other extraordinary recordings from this period include Brahms’ orchestral works and Beethoven’sViolin Concerto with Václav Hudeček as the soloist (Panton, 1986) and many works by the Czech composers Martinů, Dvořák and Smetana.

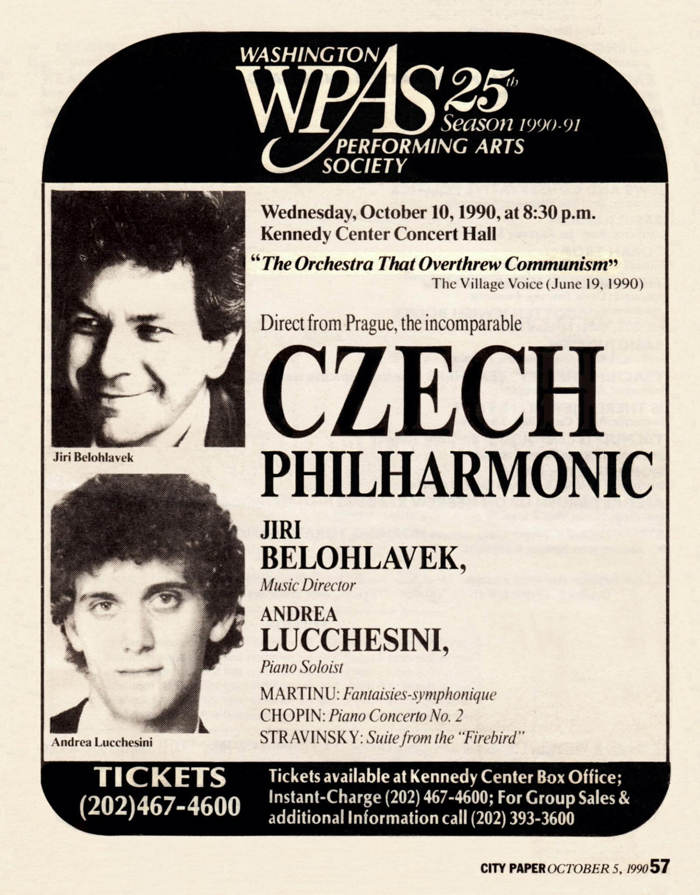

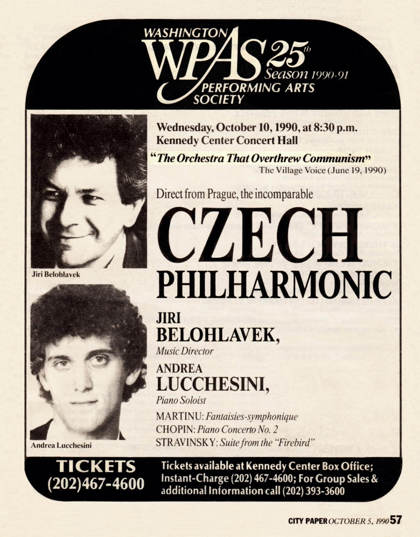

On assuming the chief conductor’s role, he took the orchestra on a month-long tour of the USA lasting from 29 September to 26 October 1990. The Czech Philharmonic, for the first time a cultural ambassador of a democratic country, presented its mastery at twenty concerts. The orchestra was warmly received not only by the general concert-going public, but also by thousands of Czechoslovak compatriots settled in the USA. The most memorable concerts included one at the Kennedy Center Concert Hall in Washington, D.C., one at Carnegie Hall in New York or the final performance of the tour – the United Nations Day concert on 24 October 1990 at the United Nations headquarters in Manhattan.

In 1990, a general reconstruction of the Rudolfinum, the seat of the Philharmonic, began. The interiors had been negatively affected both by insensitive building modifications during the First Republic, when the building served as the Parliament, and by careless use during the Second World War and the communist period. The mission of the architect Karel Prager and his team was to renovate the Rudolfinum in a way that served its original purpose – concerts of the Czech Philharmonic and visual art presentations. The reconstruction process took two years and cost 1.2 billion crowns.

The impact of the reconstruction on the concert life of Prague was fundamental. For almost three years no sounds of musical instruments could be heard there and, as a result, the Czech Philharmonic had to play concerts in the Smetana Hall of the Municipal House and go on tours abroad more intensively. In 1991 the orchestra spent 116 days and played 72 concerts abroad! [ 4 ]

The months of February and March 1991 were marked by a three-week tour of Australia, which was only the second time the Czech Philharmonic had visited the continent. The orchestra, Bělohlávek as their conductor and two soloists – Borin Krajný on the piano and Václav Hudeček on the violin - gave ten concerts in cities such as Perth, Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane. Mostly Czech music was on the programme: Smetana’s Šárka, Janáček’s Taras Bulba, Dvořák’s New World Symphony, or Martinů’s Double Concerto for String Orchestra, Piano and Timpani, diversified by works by Beethoven, Ravel and Wagner.

It is hard to think of any other well known orchestra that attacks its work – especially music that is second nature to it – with so much energy. Both the Dvorak symphony and Janacek's Taras Bulba rhapsody received convincing performances.

At the beginning of 1991, Bělohlávek signed an exclusive four-year contract with the English label Chandos and as the Czech Philharmonic chief conductor he negotiated an agreement to make most recordings with his orchestra. The label gladly accepted this. In the following years, Bělohlávek therefore recorded sixteen albums with the music of Dvořák, Janáček, Martinů, Suk, Ravel and Bartók. At the same time, he continued to record for the Supraphon label works that the Chandos label showed no interest in or works that had been commissioned by Supraphon already in 1987 to 1989.

Bohuslav Martinů’s centenary fell in 1990. To celebrate it, many recording projects were realized whose outcomes one could purchase by the end of 1990 and in 1991. Jiří Bělohlávek and the Czech Philharmonic were largely involved in many of them. They recorded two albums with his lesser-known compositions for the Supraphon label. The first album presents symphonic pieces - The Parables and Estampes for Orchestra from 1958, Rhapsody (1928) and Ouverture for Orchestra (1953). “Jiří Bělohlávek led the Czech Philharmonic towards a performance perfect in its structure and details with a sound balanced and articulate at the same time.” [ 6 ] The second album presents three compositions from the 1930s: Concerto grosso (1937), Sinfonia Concertante for Two Orchestras (1932) and Tre Ricercari for chamber orchestra (1938). These recordings were reviewed very positively as well: “The Czech Philharmonic and both pianists (Josef Růžička and Jaroslav Šaroun) present an admirable and convincing performance on this recording, which under Bělohlávek’s baton underlines the inner drive of Martinů’s music. The conductor, who has sought out the composer’s music throughout his career and has proved his skills of interpreting Martinů in countless performances, applies subtly the great art of Charles Munch that the composer himself had been so drawn to, that of a barely perceptible undulation or acceleration filled with life. [ 7 ]

Bělohlávek’s further recordings of Martinů’s work include an album of the song cycle in seven parts, strongly influenced by impressionism, Nipponari (1912), for female voice and orchestra on the words of Japanese lyrical poetry; three songs for soprano and orchestra Magical Nights (1918-1919); and Czech Rhapsody (1918) – recorded with the Prague Symphony Orchestra, Prague Philharmonic Children’s Choir and vocal soloists Jiřina Marková, Miroslav Kopp, Pavel Horáček, Dagmar Pecková and Ľubica Rybárská. Jiří and the FOK orchestra also recorded a little known ballet called The Butterfly that Stamped.

Bělohlávek took part in an event, noteworthy from the dramaturgical point of view, of a production of Martinů’s opera The Miracles of Mary staged at the Janáček Opera in Brno, which was directed by Alena Dopitová-Vaňáková, with Daniel Wiesner’s choreography and Jan Vančura’s stage and costume design. The production was well received and reviewers pointed out the very fact of this opera, long silenced and therefore unknown to the general public, being performed.

The summer months were spent relaxing and at the Music Festival in Paseky nad Jizerou which at first, in the 1980s, had been a private enterprise of an enthusiastic member of the Philharmonic, Jakub Waldmann, and his friends. In the 1990s, this festival became more official, also thanks to sponsors. In the festival’s eleventh year in 1991, such prominent figures as Václav Neumann, Jiří Bělohlávek and Ivan Kusnjer performed. In a concert held in a small church of St. Václav, Jiří Bělohlávek conducted two pieces and played the cello in others.

Bělohlávek’s second season as the chief conductor of the Philharmonic was also marked by many tours. The Rudolfinum was still under general reconstruction and the orchestra therefore focused more on international journeys. On tours, organisers required mainly music by Czech composers, especially by Antonín Dvořák whose 150th anniversary was marked in 1991. That’s why Dvořák’s music was so prominent on the tour of the UK and Ireland in September 1991 where, next to Bělohlávek as the chief conductor, Libor Pešek was the orchestra’s second conductor. The nine concerts were held in Glasgow, Nottingham, Cardiff, Leeds and Dublin and three concerts took place at London’s Barbican Hall. There, two of the concerts on 24 and 25 September were conducted by Bělohlávek with a solely Dvořák programme: Othello Overture, Cello Concerto in b minor with Lynn Harrell on the cello and The Sixth Symphony in D major. The third concert on 27 September was performed under the direction of Libor Pešek.

In preparation for the Dvořák season, Bělohlávek was aware of the danger of repertoire imbalance, he therefore focused on other than Czech composers in concerts given in Prague. He explained this step in the introduction to the 1991/1992 catalogue: “…the ensemble would be in danger of repertoire one-sidedness if we didn’t strive for a balance performing music by composers of other nationalities. That’s why in the programmes played at home, for you, our audience, we are going to balance out the repertoire we play abroad. (…) I would like to draw the attention of the Czech Philharmonic more to the heritage of classicism, with Mozart’s anniversary being a wonderful impulse. We would like to mark it not only in a one-time major concert celebration, but also by including his various compositions into all cycles of the season. We thus create a long-lasting contact with the art of interpretation of Mozart for ourselves and we present our audience with a careful selection of Mozart’s oeuvre.” [ 8 ]

In between international tours, the Czech Philharmonic gave subscription and some extra concerts at home. The performance of Verdi’s Requiem in the Smetana Hall at the Municipal House was especially memorable. The Requiemwas planned for three nights 17 – 19 October 1991. The third concert had a historical dimension in being dedicated to the Terezin Initiative, whose members are survivors of the Theresienstadt (Terezín) ghetto, and commemorated the fiftieth anniversary of the first transport of Jewish citizens of Czechoslovakia from Prague to concentration camps. The concert crowned the official visit of Chaim Herzog, the president of Israel, to Czechoslovakia. Both Herzog and the Czechoslovak president Václav Havel gave speeches before the musical part of the evening began in which they remembered the quarter of a million murdered Jews of Czechoslovakia. The international cast included the American soprano Roberta Alexander and mezzosoprano Florence Quivar, the Hungarian tenor Dénes Gulyás and the Finnish bass Jaakko Ryhänen. The choir parts were sung by the Prague Philharmonic Choir and the Prague Philharmonic Children’s Choir.

Jiří Bělohlávek laid the oratorio out as a compact fresco (without intermission) using all shades of Verdian colour spectrum, be it the Italian songful temperament, dramatic force or the secular perspective and human sympathy. (…) The Czech Philharmonic did not show the slightest signs of weariness during a short break between tours abroad and played with attentive creativity.

The Czech Philharmonic accomplished many wonderful artistic creations under the chief conductor’s baton so it seemed that their mutual collaboration would continue smoothly. However, in the course of 1991, conflicts started to appear. Discontent was building up in one part of the orchestra which together with the sense of newly-found freedom led to a legitimate demand for more say in fundamental matters concerning the orchestra and the whole institution, both artistic and financial. As far as the music direction was concerned, the statutes accepted in June 1990 enabled the orchestra members to vote for their chief conductor directly, which mirrored or rather was the result of the post-Velvet revolution ardour.

Two camps began to form in the orchestra, one of which supported the chief conductor, the other strove for a change. The latter group of musicians wanted to give preference to the German conductor Gerd Albrecht, who was the musical director of the city of Hamburg at the time. Following a performance of Dvořák’s oratorio Saint Ludmila at the Prague Spring Festival of 1991, Albrecht was approached by representatives of the Artistic Board with the question whether he would be willing to take over the orchestra if the orchestra members voted for him. The true motive for this step is known probably to the members of the delegation only. What must have been at stake though was the promise of multiple recording opportunities, better economic prospects for the orchestra with a conductor with a name and many contacts in the West, the fact that Bělohlávek was an uncompromising and demanding conductor in the professional sense, and also simply a desire for something and someone new. After some years, Bělohlávek summed it up eloquently himself:

I’d been around simply for too long in 1990. I’d been in regular contact with the members of the Philharmonic for seventeen years, they could see that I was developing as a conductor but if you observe someone continuously you notice the development only secondarily. So, in the atmosphere after 1989 when everyone was expecting new changes and impulses, my role and personality could not meet their expectations. I was one of them, everybody knew me, they knew my ways of working, the only difference being my new role of chief conductor … And I may have wanted to express myself in the role in a new way: I began to be even more demanding than before, I was really pushing for quality, trying to improve everything that was not just right.

At first, Albrecht declined the offer but then changed his mind and demanded to know the results of the internal vote as soon as possible. That is why on 15 October 1991 a secret ballot was initiated at the Municipal House, however, neither of the candidates received the minimum number of votes. The group in favour of the new chief conductor initiated a new vote soon. At the end of October 1991, the Czech Philharmonic went on a major Asian tour, visiting Japan, South Korea and Hong Kong. Concerts in Tokyo were conducted not only by Jiří Bělohlávek, but also by Václav Neumann and Rafael Kubelík. In this way, the Japanese organisers wanted to show their audience the three still living chief conductors of the Czech Philharmonic of the past fifty years. The second secret ballot was organised during the Japanese part of the tour on 26 October in Osaka. With a not very convincing number of votes Gerd Albrecht was elected the future chief conductor.

… the content of the Osaka vote was supposed to be about the extent of further collaboration with both conductors, not the actual and definite choice of one of them over the other. The majority of the orchestra members were in favour of extending the collaboration with Albrecht. However, through minor legal changes, reduction of the text and massive lobbying on the part of the Czech Philharmonic management team, this was subsequently reinterpreted and declared as the valid vote.

Despite many doubts about the legitimacy of the voting procedure, the choice was confirmed on 5 February 1992 by the Minister of Culture Milan Uhde after sixty-six per cent of the orchestra members declared that they considered the Osaka vote to be a proper election of the new chief conductor. Milan Uhde returned to this moment later in his memoirs: “The Minister of Culture only confirmed the majority’s vote by his signature, and I had no right to change anything about the decision. Before I signed it, though, I examined the reasons behind the conflict out of curiosity and I came to the conclusion that Bělohlávek’s uncompromising artistic demands was what decided it… I signed his dismissal reluctantly and apologized for it to Professor Bělohlávek in person.” [ 12 ]

In reaction, Bělohlávek resigned from the post of chief conductor. He announced his decision in an open letter addressed to the Czech Philharmonic and justified it by fundamental objections to the existing cooperation with the institution’s administration and by objections to the procedure whereby the new chief conductor was elected. He admitted that his orchestra development plan did not find as much support as he’d expected. However, given the significantly disputable voting procedure, he felt committed to those who had showed trust in him. In the letter, he assured everybody that he would fulfil all the commitments he’d made until the new music director took over. And that’s what he did fully. [ 13 ]

Following Bělohlávek’s resignation, it was necessary to fill in the period before Albrecht was ready to start his new post of music director on 1 October 1994. Václav Neumann was willing to bridge this two-year period as Chief Conductor Laureate, but he suspended this role and all collaboration with the Czech Philharmonic in March 1993 because of conflicts with the new director of the Czech Philharmonic, Milan Lášek. In the end, Gerd Albrecht took up his position with the orchestra in the autumn of 1993, a year before his originally announced appointment.

The departure of Jiří Bělohlávek was seen as a historic mistake that started a nearly twenty-year long crisis in the ensemble. Between 1992 and 1995 the newspapers were full of news about the first orchestra. There was a dispute concerning the Rudolfinum building. The orchestra’s director, Jaroslav Tvrzský, was dismissed to be replaced by Milan Lášek who stayed on the post for 166 days only. Certain mistakes, insufficient communication and personal disputes and animosities made the situation confusing not only for those involved directly but also to external observers. All this led to a change in the statutes approved by the Minister of Culture on 25 May 1993 whereby the orchestra lost the right to directly elect the chief conductor and this right was conferred on a newly established board of directors whose chairman was Ivan Medek and members were Václav Neumann, Libor Pešek, Rudolf Firkušný, Milan Slavický and representatives of the orchestra, the Ministry, and various visual arts and financial institutions. Selected in an open competition, Ladislav Kantor, a former rock musician, author of song lyrics, music dramaturg and an advisor to President Havel, became the new director. He inherited the institution and the building burdened with a massive debt that he managed to clear within one and a half years. For months, however, Kantor did not manage to find common ground with Albrecht. The complicated situation was to be resolved by establishing a new position of an “intendant” who was supposed to bridge the gap between the director and the chief conductor. It did not work out, but this chapter belongs to the administrative history of the Czech Philharmonic rather than here.

Until this collision, Bělohlávek’s career had unfolded along a straightforward path without any dramatic twists of fate. It had been filled with hard work that reaped success both at home and abroad. Therefore Bělohlávek found this new distressing situation hard to cope with and it took him a long time to get over it. He felt shattered and insecure. In retrospect, however, this professional and personal crisis turned out to be beneficial for his further career.

For a long time, I took the breakup hard. But today I can see that it was a blessing for me as I had to mobilize all my strength. I had to work very hard to ensure my place in the international competition. I would return to the Czech Philharmonic almost every season, but it did not please me. One could feel the inner conflict in the ensemble clearly and I don’t think that the collaboration pleased anyone. It was a difficult period.

After the resignation, it was a painful period for Bělohlávek, in which he had to fulfil all the commitments previously made to the Czech Philharmonic - he had to conduct all fifteen concerts on the West European tour in October 1992, for example. On the other hand, he had more time for guest conducting abroad and his agenda diary for 1992 and 1993 soon filled with various musical destinations. He conducted the BBC Philharmonic, the Philharmonia Orchestra in London, Bamberger Symphoniker, Gewandhausorchester, Orchestre National de France or the NHK Symphony Orchestra based in Tokyo. He gave concerts with Czech orchestras, too. He returned to the State Philharmonic Orchestra Brno, and in October 1993, they performed at the Europa Musicale Festival in Munich, a major parade of European orchestras with thirty-three orchestras from thirty-one countries giving concerts within one month. The programme of the Czech concert consisted of Janáček’s Taras Bulba, Martinů’s Incantation with Igor Ardašev on the piano and Dvořák’s Sixth Symphony.

Bělohlávek also took part in unusual events combining music and social outreach. In July 1992, he supported the idea of bringing music where it had been absent and, together with the Bamberger Symphoniker, opened the first year of the Mitte Europa Festival in St. John’s Church in the German town of Plauen. The goal of this Czech-German project was to bring more life to this gloomy triangle between bordering parts of the Czech Republic, Saxony and Bavaria and promoted the idea of friendly cohabitation of neighbours under the motto of "Let insurmountable borders never arise again". [ 15 ]

At the concert, one could enjoy the music of Antonín Rejcha’s Overture in C, Dvořák’s Czech Suite and Beethoven’s Second Symphony.

In this period, Bělohlávek conducted the Czech Philharmonic also at the Prague Spring Festival 1992. The concert was significant as it “reopened” the Rudolfinum building for musical life on 15 May 1992 after three years of general reconstruction. Together with the pianist Rudolf Firkušný, they played works by Dvořák, Suk and Janáček.

Other concerts with the Czech Philharmonic included two opening concerts of the ninety-seventh season with the programme of Bartók’s Divertimento, Brahms’ First Piano Concerto with Rudolf Firkušný as the soloist and Martinů’s Fourth Symphony. The concert was an extraordinary event especially as Firkušný, even at his advanced age, continued to amaze everybody with his virtuosity and artistic depth. “One must say that this corypheus of piano interpretation surpassed all expectations and his performance was unforgettable and unique, comparable only with the greatest artistic creations. Even at his advanced age, Firkušný is equal to the demanding task, not only in the natural flawlessness of his technique, but also in managing to reveal the full multifaceted expressiveness of Brahms' music in an incredible way. (…) Bělohlávek and the orchestra contributed to the harmonic and relaxed collaboration with the soloist.” [ 16 ]

One could feel throughout the review the author’s unspoken pity caused by the recent events in the orchestra, but also his joy that Bělohlávek “continued to be attached to the Czech Philharmonic through intensive collaboration and to be the one whom the orchestra owes many excellent performances…” Rudolf Firkušný donated his fee from both concerts in favour of the Olga Havel Foundation “Výbor dobré vůle” (Goodwill Committee) and to the Václav Havel Foundation. Bělohlávek donated his fee for one of the concerts to the Czech Philharmonic. Right after the opening concert, the Czech Philharmonic went on a tour of Germany, the Netherlands, and Belgium.

In April 1993, Bělohlávek received an annual prize of the Czech Music Fund for his recording of Suk’s Symphony in c minor “Asrael” recorded with the Czech Philharmonic for the Chandos label. In October 1993, a festival of Czech music was held in London. The city was literally flooded with Czech music and musicians. The festival was opened by Jiří Bělohlávek and the Czech Philharmonic performing Smetana’s Má vlast. And the final night belonged to Bělohlávek as well, when he conducted Janáček’s Glagolitic Mass with the London Philharmonic Orchestra and Choir and two Czech soloists, Eva Urbanová and Dagmar Pecková. Throughout the festival, reviews sang odes to Czech musicians. They appreciated for example Bělohlávek’s rendering of Dvořák’s Eighth Symphony as the kind of performance that Britain dreams of. In reviewing the final concert, the Times expressed the wish “to see Bělohlávek more and more often.” [ 17 ]

The wish soon came true, not only thanks to this triumph.

In the early 1990s, Bělohlávek opened another chapter of his professional life by starting to teach. In 1990, during his winter holiday stay in the Krkonoše mountains, he met a young musician Tomáš Hanus. “I told him then that I would love to become a conductor but that it was very difficult to find a good mentor. And he said he was willing to have a look at me from time to time. When he was approached by the Janáček Academy of Performing Arts in Brno, he became Professor there externally – only to oblige me. He had no other student there.” [ 18 ]

Tomáš Hanus not only played in Bělohlávek’s life the role of his first, talented and attentive student, but their meeting would significantly determine Bělohlávek’s subsequent professional direction and make a very positive impact on Czech musical life.

Main sources

- 1.

HARTMAN, Ivan; KONRÁD, Daniel: Jiří Bělohlávek: Dalšího Martinů zatím nevidím. Hospodářské noviny. 2012. 4. 10. Available online

- 2.

SKÁLOVÁ, Zuzana: Něco jsem se načekal. S Rudolfem Firkušným o domově a cizině. Lidové noviny 3, 1990, č. 245 (vydání Praha, 19. 12.), s. 8.

- 3.

MLEJNEK, Karel: Česká filharmonie. Deset kapitol ze stoleté historie orchestru. Praha: Česká filharmonie, Paseka 1996, s. 110.

- 4.

KOLÁČKOVÁ, Yvetta a kol: Česká filharmonie 100 plus 10. Praha: Academia 2006, s. 124.

- 5.

O'CONNELL, Clive: Czech orchestra plays to many empty seats. The Age, 1991 (4. 3.). Za vyhledání a zprostředkování pramenů děkujeme paní Evě Breward.

- 6.

SMOLKA, Jaroslav: Symfonický Martinů slavný i neznámý. Gramorevue 27, 1991, č. 3., p. 10.

- 7.

MATZNER, Antonín: Martinů známý i neznámý. Gramorevue 27, 1991, č. 8. s. 7.

- 8.

BĚLOHLÁVEK, Jiří: Úvodní slovo. In Programový sborník České filharmonie 1991/1992. Praha: Česká filharmonie 1991.

- 9.

BOR, Vladimír: Verdiho Requiem in memoriam. Hudební rozhledy 1991, č. 12, s. 543–544.

- 10.

VEBER, Petr, STEHLÍK, Luboš: Jiří Bělohlávek. Fluidum, nebo práce? Harmonie2016, č. 2, s. 6–15. Available online

- 11.

MLEJNEK, Karel: Česká filharmonie. Deset kapitol ze stoleté historie orchestru. Praha: Česká filharmonie, Paseka 1996, s. 111.

- 12.

UHDE, Milan: Rozpomínky. Co na sebe vím. Torst a Host, Praha a Brno 2013, s. 521.

- 13.

BARANČICOVÁ, Svatava; SLAVÍKOVÁ, Jitka, VEBER, Petr: Zahraniční dirigenti v čele československých orchestrů. Hudební rozhledy 1992, č. 4. s. 149.

- 14.

HARTMAN, Ivan; KONRÁD, Daniel: Jiří Bělohlávek: Dalšího Martinů zatím nevidím. Hospodářské noviny 2012, 4. 10. Available online

- 15.

Author unknown: Festival české a německé kultury. Rudé právo 2, 1992, 27. 7., č. 174, s. 4.

- 16.

KAŠPÁREK, Ludvík: Velkolepý úvod filharmoniků. Lidová demokracie 48, 1992, č. 224 (23. 9.), s. 4.

- 17.

Taken from SMACZNY, Jan: Horečka české hudby v říjnovém Londýně. Hudební rozhledy 1993, č. 12, s. 567.

- 18.

VEBER, Petr: Tomáš Hanus. Dirigent stojící na obou nohou. Harmonie 2017, č. 12, s. 14.

HARTMAN, Ivan; KONRÁD, Daniel: Jiří Bělohlávek: Dalšího Martinů zatím nevidím. Hospodářské noviny. 2012. 4. 10. Available online

SKÁLOVÁ, Zuzana: Něco jsem se načekal. S Rudolfem Firkušným o domově a cizině. Lidové noviny 3, 1990, č. 245 (vydání Praha, 19. 12.), s. 8.

MLEJNEK, Karel: Česká filharmonie. Deset kapitol ze stoleté historie orchestru. Praha: Česká filharmonie, Paseka 1996, s. 110.

KOLÁČKOVÁ, Yvetta a kol: Česká filharmonie 100 plus 10. Praha: Academia 2006, s. 124.

O'CONNELL, Clive: Czech orchestra plays to many empty seats. The Age, 1991 (4. 3.). Za vyhledání a zprostředkování pramenů děkujeme paní Evě Breward.

SMOLKA, Jaroslav: Symfonický Martinů slavný i neznámý. Gramorevue 27, 1991, č. 3., p. 10.

MATZNER, Antonín: Martinů známý i neznámý. Gramorevue 27, 1991, č. 8. s. 7.

BĚLOHLÁVEK, Jiří: Úvodní slovo. In Programový sborník České filharmonie 1991/1992. Praha: Česká filharmonie 1991.

BOR, Vladimír: Verdiho Requiem in memoriam. Hudební rozhledy 1991, č. 12, s. 543–544.

VEBER, Petr, STEHLÍK, Luboš: Jiří Bělohlávek. Fluidum, nebo práce? Harmonie2016, č. 2, s. 6–15. Available online

MLEJNEK, Karel: Česká filharmonie. Deset kapitol ze stoleté historie orchestru. Praha: Česká filharmonie, Paseka 1996, s. 111.

UHDE, Milan: Rozpomínky. Co na sebe vím. Torst a Host, Praha a Brno 2013, s. 521.

BARANČICOVÁ, Svatava; SLAVÍKOVÁ, Jitka, VEBER, Petr: Zahraniční dirigenti v čele československých orchestrů. Hudební rozhledy 1992, č. 4. s. 149.

HARTMAN, Ivan; KONRÁD, Daniel: Jiří Bělohlávek: Dalšího Martinů zatím nevidím. Hospodářské noviny 2012, 4. 10. Available online

Author unknown: Festival české a německé kultury. Rudé právo 2, 1992, 27. 7., č. 174, s. 4.

KAŠPÁREK, Ludvík: Velkolepý úvod filharmoniků. Lidová demokracie 48, 1992, č. 224 (23. 9.), s. 4.

Taken from SMACZNY, Jan: Horečka české hudby v říjnovém Londýně. Hudební rozhledy 1993, č. 12, s. 567.

VEBER, Petr: Tomáš Hanus. Dirigent stojící na obou nohou. Harmonie 2017, č. 12, s. 14.