“It is the best that I have experienced with the Czech Philharmonic. And it falls in the highest category I have ever experienced in my entire career. And I am delighted that it happens here, at home and with this particular orchestra. Since the Czech Philharmonic is an ensemble closest to my heart, it is where I grew up artistically as Václav Neumann’s assistant.”

The second chapter of Jiří Bělohlávek’s chief conducting with the Czech Philharmonic started in 2010. In August, the Ministry of Culture invited applications for the position of general director of the institution. David Mareček, the then thirty-four-year-old director of Filharmonie Brno, was also invited to apply. He and his colleague Robert Hanč started to consider this offer and addressed Bělohlávek directly with their vision: “David and I thought that we would take part in the competition provided we could convince Jiří Bělohlávek to be part of it, because you cannot run an orchestra without an excellent and outstanding chief conductor. Our first steps were therefore to contact him, meet him and ask if he’d be interested. Only his answer meant a clear yes for us.” [ 2 ]In this way, Bělohlávek took an active advisory role already while developing the conception with which David Mareček succeeded in October 2010.

At the beginning, there were long meetings in Souvrať where, eating raspberries hand-picked by Jiří and prepared by Anna, we were thinking through our plans to do it all so that it would work. Then there were Jiří’s visitations with the culture and finance ministers and his adamant fight for better conditions for the musicians. And talks about repertoire, recording possibilities, tours and about ways in which to rehearse and work with the orchestra. And then endless negotiations with the orchestra members, ministries, agents. Convincing the international partners that the Czech Philharmonic was about to enter a happy era in which it would be a joy to come and listen to their concerts.

David Mareček suggested Jiří Bělohlávek as the new chief conductor of the Czech Philharmonic already in his conception and following his appointment as the institution’s general director he helped to negotiate the conditions for Bělohlávek’s position. The orchestra’s interim management and the Ministry of Culture were interested in engaging Bělohlávek, as can be seen from the fact that he was the only candidate participating in the negotiations. These were intensive and Bělohlávek and the newly appointed management were able to raise enough funds for the intended reform for years to come. For Bělohlávek, a crucial signal was given when the Artistic Board supported the whole conception of overall reform and was willing to overcome the period of stagnation.

Even despite the painful departure from the post of Czech Philharmonic’s chief conductor in 1992, Bělohlávek considered leading this orchestra the highest thinkable achievement for a Czech conductor. For that reason, he refused several offers from prestigious European and American ensembles and decided to step into the same river for the second time. The river, however, was not really the same. Bělohlávek wouldn’t have made the step, if he hadn’t felt from his collaborators a strong desire for change. He had been offered the position of the chief conductor by some previous directors of the Czech Philharmonic – but the situation had never been acceptable for him in the sense of enabling him and the orchestra to strive for the highest artistic quality possible.

I imagine my upcoming engagement as the chief conductor of the Czech Philharmonic as the crowning of my artistic career; in this way I am returning to my roots from which I came as a conductor and where I would like to put to good use all the fruits of my life-long experience.

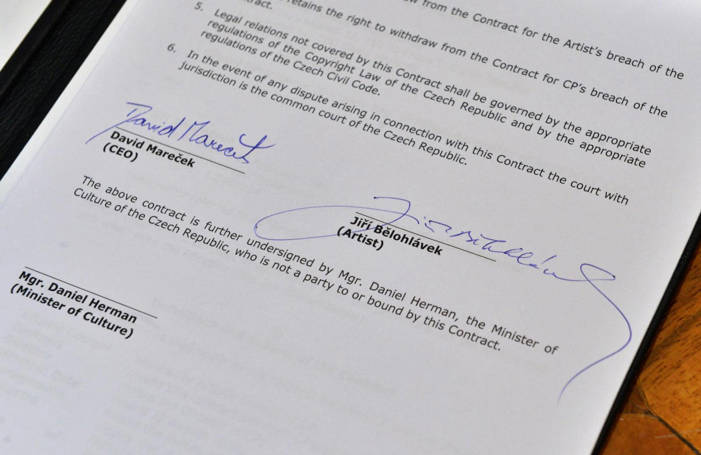

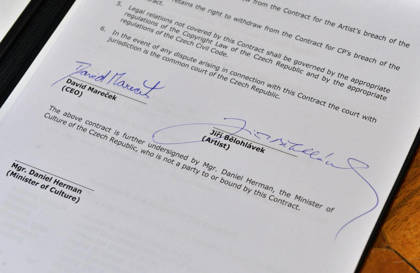

Jiří Besser, the Minister of Culture, signed the contract with Jiří Bělohlávek on 22 December 2010. The conductor was to take up his new post in autumn 2012, when the mandate of the Israeli conductor Elijahu Inbal ended. Experts saw Bělohlávek’s appointment as an excellent step for further developments of the orchestra and agreed that it was the best way to make the orchestra more stable, artistically and socially enhanced and to strengthen its prestige internationally.

I am convinced that the Czech Philharmonic is at ninety-five per cent of undisputable high quality given by the standard of the players. My task is to heat up this potential and get it moving so that it can reach, and surpass, the performative level we were used to hearing in the past.

The Czech Philharmonic benefited from Bělohlávek’s reputation immediately after his arrival was announced. The situation when a top Czech orchestra appoints a renowned Czech conductor was perceived as the Philharmonic’s return to the roots from which it grew: to the characteristic sound associated with the Czech musical environment and Czech artists. Following the appointment, there was a sudden increase in demand for the Czech Philharmonic in the most famous halls of major cities around the world, and so even before Bělohlávek’s first season began, the orchestra had touring plans until 2015 with such stops as the Carnegie Hall in New York, the Proms festival in London, Suntory Hall in Tokyo, and Vienna’s Musikverein.

The chief conductor’s contract stated that the orchestra’s management and Bělohlávek will agree on details of the chief conductor’s artistic and other obligations and will present plans for improvement of their future collaboration within the following six months. In 2011 and 2012 they were therefore working on specifying the conception and were introducing a whole range of changes in the organisation and administration of the institution and the ensemble.

Bělohlávek conditioned his return by improvement in remuneration of the orchestra’s players. Their salaries had to ensure that the musicians could devote their work time fully to the artistic mission, to focus on practice at home, on rehearsals and concerts. The salaries were raised and therefore also the demand for higher personal responsibility of each player. The rights and obligations of the orchestra members were redefined, and a precise procedure for assessing artistic quality was established.

The rehearsal and concert scheme was also altered. Since the 2012/2013 season, subscription concerts have included a premiere and two repeat performances. These three concerts usually take place on a Wednesday, Thursday and Friday. Thanks to this change, more people could hear the programme and the orchestra gained one more performance, which was useful when the programme was recorded. This change, however, also meant that the players became busier – by thirty percent in the subscription week, and there was less time for rehearsals and more pressure on individual practice and preparation.

The important thing was that all these steps were approved by the internal bodies of the orchestra: the Artistic Board, the management and the unions. It was a result of an open discussion in which everybody concerned took an active part.

Moreover, Bělohlávek returned the position of the music director of the Czech Philharmonic to the Rudolfinum, a position that Bělohlávek initiated already when he was the chief conductor for the first time at the beginning of the 1990s and that, following the approval of the orchestra’s management and representatives of players, he reintroduced for his second period. The position anchored and manifested the unified artistic management of all parts of the institution and at the same time it established the conductor’s full commitment to the orchestra.

However, it meant no establishment of autocracy. The Artistic Board and the management were equal partners of the Music Director and all important decisions were made together. The profile of the orchestra and concert seasons gained united contours in this way. As Bělohlávek explained: “The conductor should give the orchestra enough time and energy so that he can be the one responsible for the artistic quality of all the productions presented under the name of the Czech Philharmonic. I am convinced that it is right and necessary so.” [ 6 ]

Bělohlávek’s activities evolved in depth and breadth in this spirit of full focus on the orchestra, and not only in the sense of interpretation, rehearsals and concerts, but also in the long-term care for sound and expressive qualities of the orchestra, including intonation, internal ensemble, tone quality and the richness of the orchestra’s expressive palette. Bělohlávek was involved also in the process of selecting new musical instruments for purchase. An important area of Bělohlávek’s involvement was the dramaturgy of individual seasons and establishing collaboration with conductors and soloists from abroad.

My idea of artistic work is quite distinctive and clear: I have forty years of experience in which I developed a certain ideal of interpretation, sound, quality of playing and approach to music in general – and that’s what I would like to bring to the ensemble. There are no miraculous recipes – I mean it is the humblest approach to everyday artistic work and I am convinced that in the ensemble, which I am looking forward to working with, there is an amazing potential but also unbelievably many shortcomings. I would like to disclose them and bring them to light.

Furthermore, there were issues concerning the exchange of generations of players and of maintaining a unified musical profile of the orchestra. After an extensive discussion with representatives of the orchestra’s instrumental groups, a new audition code was developed, which expanded the audition committee significantly. The first year in the orchestra was agreed to be a probationary period for each musician, in this way one could see whether the manner of playing, the work commitment, but also the personal qualities of the player correspond to the standards required by the Czech Philharmonic.

Bělohlávek also engaged intensively in attracting young talents and players interested in playing in a symphonic orchestra (Orchestral Academy) and in educating new generations of listeners (education programmes). Additionally, he dealt with issues concerning the orchestra’s presence on the recording market, publicity at home and abroad and other topics.

Jiří Bělohlávek lived here with us. He was unique in the fact that when he got appointed, he resigned from most of his commitments abroad. He taught us what it meant when a chief conductor was building an orchestra. He went to see the auditions, which is not done by all conductors. He went to see rehearsals of other conductors observing what a guest captain can do with his team, which is not done by any conductors. He was a top professional as a conductor, but he was also deeply involved also in the organisation and programme, he represented the institution. He pushed us to work as fast as we could and he himself set an example.

The opening concerts of the 117th season on 4 and 5 October 2012 drew a lot of attention, and not only thanks to publicity activities of high quality. Several interviews with Bělohlávek and the orchestra’s management appeared in the media and experts and critics had words of praise for the orchestra, speaking about the dawn of a new era and of it being on the way to become one of the top ensembles in the world. The first opening concert was broadcast live by the main media partners – Czech Television and Czech Radio.

Bělohlávek chose the programme of the opening, and at the same time inauguration, concert in a way that presented the orchestra’s qualities fully in various styles and positions and anticipated the orchestra’s future programme directions. The programme included Petr Eben’s symphonic movement Vox clamantis that demonstrated the orchestra’s focus on contemporary music, Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony representing the repertoire of the classicist and romantic periods, Mahler’s Five Early Songs arranged by Luciano Berio sung by the baritone Gerald Finley representing intended international collaboration, and finally Janáček’s Sinfonietta giving the orchestra a chance to show their virtuosity and musicality.

The festive atmosphere of the evening was intensified by the presence of many important guests in the audience and by orange daisies in the players’ lapels. Not only the conductor, but also the positioning of the instrumental groups was new. Bělohlávek changed the layout used until then so that the double-bass players were seated in one row at the back of the orchestra, and the brass and percussions appeared on the right side of the stage. The reviews agreed that “Jiří Bělohlávek achieved a much denser and more impressive orchestra sound that benefited all four performed pieces.”

The star of the evening was the Canadian baritone Gerald Finley in Mahler’s Five Early Songs arranged by Luciano Berio. Such soulful interpretation, perfect in expression, has not been heard here for a long time. (…) Among the orchestral works, Beethoven’s Fifth was especially noteworthy in exemplary interpretation of unusual percussiveness. (…) Let’s conclude on a happy note – the evening hinted at the best, which was confirmed by the following concerts.

Jiří Bělohlávek and the Czech Philharmonic found a common tongue. That is the main message of the two inauguration concerts of 4 and 5 October at the Rudolfinum. A common tongue does not necessarily mean that the performance was simply brilliant and flawless. However, we witnessed a rare moment when the enthusiasm of the conductor and the orchestra intersected and was mutually intensified.

An almost identical programme (excluding Mahler’s songs) was performed soon after at the first concert the Czech Philharmonic and its new chief conductor gave abroad, in Slovakia quite symbolically. On 6 October they performed at the Bratislava Music Festival.

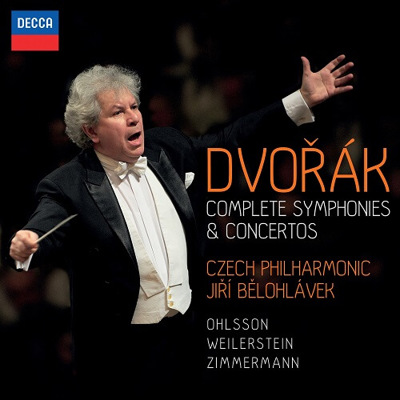

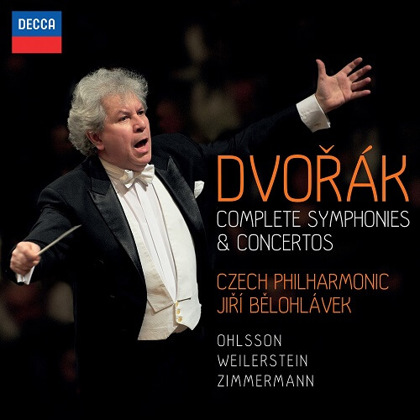

In the first season, there were some exceptional events and the biggest recording project in the history of the Czech Philharmonic. The orchestra under Bělohlávek began to record all of Antonín Dvořák’s symphonies in the autumn of 2012. They recorded symphonies nos. 1, 3, 5, 6, 7 and 8 at subscription concerts already in November. In the summer of 2013, they recorded the Cello Concerto and the Piano Concerto in a studio, and in the autumn, they recorded symphonies nos. 2, 4 and 9 and the Violin Concerto. Top international musicians took the solo parts: Alisa Weilerstein – cello, Garrick Ohlsson – piano and Frank Peter Zimmermann – violin. The complete set was released by Decca Classic in August 2014.

The task is different in the sense that it is to be a complete symphonic set recorded after twenty-five years. I see in it as one of the greatest challenges of the first seasons. I have never before conducted the First, Second and Third Symphony. And it is a known fact that they are problematic. I have been lying in the scores for six months now so that I can do it well. Dvořák’s early symphonies are very long and are not yet masterpieces of the highest kind – we must do them in such a way that is true to the original and at the same time gains most of it and makes it accessible and vivid for today’s audience. That is no simple task.

Filming live performances of all the symphonies was part of the project. It was broadcast on Czech TV and later made into a DVD where Jiří Bělohlávek’s and Marek Eben’s commentary was added. A time-lapse film Objevování Dvořáka (Discovering Dvořák) was made by the Canadian director Barbara Willis Sweete, the author of live broadcasts from the Metropolitan Opera. Throughout two seasons, she and her team followed the recording process, the changes in the orchestra and the players’ relationship with their chief conductor.

In the area of education, Bělohlávek got involved in a series of educational programmes for adults, young listeners and children. In the programme entitled Mohlo to znít úplně jinak (It could have sounded quite differently) directed by Alice Nellis, one could be part of an open concert rehearsal with commentary by Jiří Bělohlávek and the actor and presenter Marek Eben. In the first half, they analysed and performed the second movement of Mahler’s Seventh Symphony, and after intermission the overture from Johann Strauss’ operetta Die Fledermaus. Programmes with Jiří Bělohlávek and Marek Eben continued in the following seasons and concluded in a whole series of popular programmes called Zkouška orchestru (An Orchestra Rehearsal). Many of these concerts with commentary were filmed by Czech TV. An overview of the programmes from years 2012/13 to 2017/18 was prepared by the head of educational programmes, Petr Kadlec. You can read through his memories of The Reahearsal of the Orchestra in an article attached here.

In March 2013, the Czech Philharmonic visited the United Arab Emirates for the first time ever when it performed at the tenth year of the prestigious Abu Dhabi Festival. They gave three concerts there and collaborated with real stars. On 20 March at the Emirates Palace Auditorium, they played Richard Wagner, Giuseppe Verdi and Leonard Bernstein under the baton of Eugen Kohn and accompanying Ana María Martínez and Plácido Domingo. The next two concerts, conducted by Bělohlávek, offered compositions by Dvořák and Smetana. The soloist of the first of the concerts was the violin virtuoso Joshua Bell. In the second concert, the Czech Philharmonic accompanied baritone Bryn Terfel and soprano Victoria Yastrebova.

Another tour of the Czech Philharmonic and Jiří Bělohlávek took place soon after in April. This time England was their destination with stops in Birmingham, Edinburgh, Basingstoke, Cardiff and Nottingham. The programme included works by Dvořák, Beethoven and Smetana. The solo parts were performed by the French pianist Hélène Grimaud, the British pianist Freddy Kempf and the then concertmaster of the orchestra Josef Špaček Junior.

…this concert suggested that his return to the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra as music director has brought him back to his emotional and musical heartland. In works by Dvořák and Smetana, unbounded lyricism and Czech melancholy emerged with the authenticity that only this orchestra can bring, and they delivered with discipline. It certainly lived up to the memory of their visit to St David's Hall with Bělohlávek at the helm more than two decades ago. Now, with a mane of white hair to rival that of his compatriot Leoš Janáček, Bělohlávek's energy is undiminished.

…tento koncert prokázal, že pro Bělohlávka byl návrat na post šéfdirigenta České filharmonie také návratem do krajiny jeho srdce, a to emocionálně i hudebně. V Dvořákových a Smetanových dílech byly slyšet nespoutaná lyričnost a česká melancholie s takovou autenticitou, jaké je – a v tomto případě také byl - schopen právě jen tento orchestr. Rozhodně dostál očekáváním vzbuzeným vzpomínkou na jeho předchozí vystoupení v St David’s Hall v čele s Jiřím Bělohlávkem před více než 20 lety. Nyní, s hřívou bílých vlasů, která by se dala měřit s hřívou jeho krajana Leoše Janáčka, Bělohlávek srší stále stejnou energií.

In May 2013, subscription concerts of the A Cycle hosted the Finnish soprano Karita Mattila. Although they had collaborated many times at renowned opera houses in the world, this was the first performance of Bělohlávek and this world-famous singer in the Czech Republic. Karita Mattila sang the famous aria of Isolde dying of love from Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde.

In the second week of June, the Czech Philharmonic was a guest at the Smetanova Litomyšl Festival, performing Smetana’s Má vlast twice under the baton of Jiří Bělohlávek on Thursday 13 June and Friday 14 June.

A natural leader of the orchestra, the moment he raises the baton, he gets the players’ full commitment and manages to lead them to depth of thought and rich sonority of Smetana’s composition. Bělohlávek was anchored in the traditional interpretation, proven by time, nevertheless knowing the score perfectly he also showed the dramatic and multifaceted quality of the symphonic cycle, he used a large palette of expression and dynamics with all elegance and temperament … The conductor asked for the performance of Má vlast being performed without intermission, so the work sounded like Smetana’s genuine symphonic statement of the highest musical quality…

Bělohlávek’s first season with the Czech Philharmonic was concluded in an open-air concert. The first ever open-air concert of the orchestra took place on 21 June 2013 at the Old Town Square in Prague and was intended for general public. The varied programme included compositions by Vivaldi, Dvořák, Smetana and Bernstein. The concert had a special guest - Bobby McFerrin.

When assessing his first season with the Philharmonic in the autumn of 2013, he could easily call it a success. The fact that he and the orchestra got to understand each other so quickly surprised both him and others: the way in which their mutual understanding got deeper with every concert and the orchestra followed his conducting more and more sensitively.

I came with great expectations and enthusiasm, and I could feel that my new collaborators felt the same way. And I think that these two expectations, these two energies that wanted to start to work together joined beautifully. I can say that the whole season was immensely encouraging for me, immensely inspiring and practically all our performances were moved by a fantastically creative and thriving spirit.

Before the start of his second season, Bělohlávek, the Czech Philharmonic and the cellist Alisa Weilerstein opened the sixth year of the Dvořák Prague International Music Festival. On 10 September 2013, the programme consisted of Adagio from Penderecki’s Third Symphony, Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony and Dvořák’s Cello Concerto, which is traditionally the opening work of the festival.

Later in September, Bělohlávek had his first performance with the Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra as the principal guest conductor, which he became for the period of four years. In Rotterdam he performed a total of thirteen different programmes in the following years, which included works by Antonín Dvořák, Bohuslav Martinů and other Czech composers, as well as works by Gustav Mahler and Ludwig van Beethoven.

The Czech Philharmonic under Bělohlávek’s baton opened their 118th season on 3 and 4 October 2013, performing Janáček’s Glagolitic Mass in its original version from 1927. Two top Russian soloists also appeared on the stage of the Rudolfinum. Sergei Nakariakov, also known as “Paganini or Caruso of the trumpet” and Alexander Melnikov, a pianist specialising in the Shostakovich repertoire.

This first of Leoš Janáček’s versions draws attention due to its expressiveness; it may be even more audacious and raw, introducing unusually simultaneous counterpositions of various rhythmic models, and different rendering of several key places. This version of the Mass was enthusiastically received and drew exceptional attention when I performed it with the BBC Symphony Orchestra in London at the opening night of the Proms in 2011.

In October and November 2013, the Czech Philharmonic and their chief conductor went on a tour to Japan with concerts in six Japanese cities. The programme consisted of Dvořák, Brahms, Glinka, Beethoven and Russian classics – Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninov. Solo parts were performed by the cellist Narek Hakhnazaryan, pianist Hisako Kawamura, violinists Isabelle Faust and the concertmaster of the Czech Philharmonic Josef Špaček.

The Czech Philharmonic Orchestra led by Jiří Bělohlávek opened the Year of Czech Music 2014 with a festive New Year concert on 1 January 2014. At the beginning of the concert they played the first part of Suk’s Fairy Tale op. 16 entitled About the Constant Love of Raduz and Mahulena and Their Trials, followed by compositions by Bohuslav Martinů, Bedřich Smetana, Leoš Janáček and Oskar Nedbal. The world premiere of Dvořák’s Love Songs arranged for a symphonic orchestra by Jiří Teml and sung by the mezzosoprano Magdalena Kožená was the night’s climax.

Every ten years, the Year of Czech Music marks important anniversaries of important personalities of Czech music (Smetana, Dvořák, Janáček, Suk, Zelenka and others). In 2014, Magdalena Kožená together with her husband Sir Simon Rattle were the Year’s artistic patrons. The Czech Philharmonic joined this cultural initiative with more than a hundred events. Works of Czech composers could be heard in both subscription cycles at home and in concerts in European and Asian cities and at various festivals in Europe, including the BBC Proms.

In January and February, Bělohlávek brought Czech music to Austria. In Vienna’s Staatsoper he conducted a production of Dvořák’s Rusalka, directed by Sven-Erik Bechtolf. The performance featured the Bulgarian soprano Krassimira Stoyanova as Rusalka, Michael Schade as the Prince, Günther Groissböck as the Water Goblin and Janina Baechle as Ježibaba. It was Bělohlávek’s debut at this famous opera house. He conducted an opera once again in April. He staged Tchaikovsky’s Queen of Spades which was directed by Robert Carsen and had its premiere on 6 April 2014 at the Zurich Opera House.

The success of the evening is also due to the formidable conducting of Jiří Bělohlávek who can create wonderfully suspended atmospheres in the preludes (or in the scene between Pauline and Lisa) but can also maintain exciting dramatic tension when necessary. The orchestra’s colours are captivating, especially in the wind section.

Úspěšnosti večera napomáhá rovněž úžasné vedení Jiřího Bělohlávka. Vytváří obdivuhodné atmosférické obrazce patrné v předehře (nebo ve scénách mezi Pauline a Lisou), ale umí zároveň udržet vzrušující dramatické napětí tam, kde je to potřeba. Orchestr zaujme svou barevností, především v dechové harmonii.

In co-operation with others, Bělohlávek initiated and actively organized many projects supporting young talents. One such project was Zahraj si s Českou filharmonií (Play with the Czech Philharmonic) for musicians under 21. A committee consisting of the chief conductor and players of the Philharmonic chose eleven young musicians at an audition. Seven of them performed in a concert on 29 January at the Rudolfinum. This “Concert of Talents” was broadcast by Czech Radio 3 – Vltava. The remaining four appeared in the final open-air concert on 24 June at Hradčanské náměstí.

I understand the idea to invite young musicians to audition last year for the opportunity to play with the Czech Philharmonic in June 2014 as a part of our institution’s general mission to inspire young people to listen to and make music. I believe that this in a way rare event can attract those people who have not yet found their way to concert halls.

Further, the Czech Philharmonic announced a competition for young composers under 35. Twenty-nine promising young musicians took part in the competition, in which their task was to compose a symphonic piece no longer than fifteen minutes which had not been performed yet. Jan Ryant Dřízal was the winner with his composition Kuře melancholik (The Melancholic Chicken). A special Prize of the Chief Conductor of the Czech Philharmonic Jiří Bělohlávek was awarded to David Lukáš for his composition Zrození světla (The Birth of Light). The prize of the chairman of the jury Miroslav Srnka was given to Slavomír Hořínka for his piece Kapesní průvodce letem ptáků (A Pocket Guide to the Flight of Birds).

The winning composition, Kuře melancholik, was performed by the Czech Philharmonic and Jiří Bělohlávek in a subscription concert in October 2015. The two other awarded compositions were performed by the orchestra in a non-public rehearsal under Bělohlávek’s assistants Vojtěch Jouza and Ondřej Vrabec with both authors, Miroslav Srnka and Jiří Bělohlávek present. Srnka and Bělohlávek anchored it in the rules of the competition that the awarded authors would get a chance to hear their piece played live and to obtain a recording of it.

I was so pleased to see the orchestra showing so much interest in making it happen even though learning two unfamiliar pieces in such a short time can be no other than imperfect in principle. However, it was a decent interpretation enabling both authors to hear clearly how their imagined work translated to reality.

Bělohlávek’s involvement in the education activities of the Czech Philharmonic continued and expanded both in quality and quantity in the 118th season. In February 2014, the Czech Philharmonic organized Carnival for children at the Rudolfinum offering music workshops, games and guided tours of the backstage. The whole event was concluded by a fairy tale concert conducted by Bělohlávek, alias Wizard Bělokněžník. In addition, Bělohlávek took part in the above-mentioned education programme for adults, Zkouška orchestru.

In the first half of 2014, the orchestra and Jiří Bělohlávek gave concerts in European cities. In February, they performed in Ljubljana, Udine, Zagreb, Zurich, Basel and Berlin. Apart from the last concert of the tour, the orchestra accompanied the pianist Nikolai Lugansky, who alternated between S. Rachmaninov’s Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. 2 and F. Chopin’s Piano Concerto No. 2. In Berlin, Hélène Grimaud took over and played Brahms’ Piano Concerto No. 1. In addition, the orchestra played compositions by Bedřich Smetana and Antonín Dvořák.

At the end of May 2014, the Czech Philharmonic conducted by Bělohlávek went on a tour of China and South Korea. Their first concert on the tour was in Seongnam in South Korea. They played twice at the prestigious National Centre for the Performing Arts in Beijing and at other major concert halls in Chinese cities – Hong Kong, Shanghai, and Kanton. Every concert included Czech compositions such as Smetana’s Vltava, Dvořák’s Sixth and Ninth Symphony or Martinů’s Fourth Symphony. The orchestra accompanied the pianist Paul Lewis in several concerts, performing Brahms’ Piano Concerto No. 1 in D minor and Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 3 in C minor.

Still before going on the tour, the Czech Philharmonic together with Jiří Bělohlávek opened the 69th Prague Spring International Music Festival. The performances were innovative in many ways. First, there were three performances - on 12, 13 and 14 May - unlike the usual two, second, they played it without the traditional intermission after Šárka. Moreover, Bělohlávek expanded the orchestra substantially, doubling most of the instruments, for Vyšehrad there were six harps on the stage. All concerts were recorded, and the recording was released on Decca Classic label in January 2018.

Jiří Bělohlávek has managed to provide Smetana’s music with a unique quality: radiating perfection, modest romantic singing-like quality and soft warmth, rich variability, simple tranquillity and festive beauty. (…) Bělohlávek’s Má vlastwith the conscientious and rich playing of the orchestra sounded intimately familiar, with many details that next to the expected moments open our eyes and ears to new experiences. It sounded like a thoroughly vivid exceptional score of our and European music.

This recording of Má Vlast (…) is the orchestra’s tribute to one of its best-loved conductors and makes a perfectly apt memorial. They had made a much earlier recording of Má Vlast together, in 1990 for Supraphon, but the new version has a much warmer, richer and more detailed sound than its predecessor. The orchestral playing on this later performance has a fraction more depth and personality too; the CPO has always been an exceptionally characterful band, and under Bělohlávek they seem to have added muscularity and incisiveness to that mix.

Touto nahrávkou Mé vlasti (…) vzdává orchestr hold jednomu z nejmilovanějších dirigentů a buduje mu tím patřičný pomník. Orchestr s Bělohlávkem natočil Mou vlast již mnohem dříve, v roce 1990 pro Supraphon, ale toto nové provedení má mnohem vřelejší, bohatší a preciznější zvuk než zmiňovaný předchůdce. Hra orchestru na této pozdější nahrávce je nepatrně niternější a osobitější. Česká filharmonie byla vždy výjimečným souborem plným charakterů a pod Bělohlávkovým vedením k této směsi přidali ještě svalnatost a pronikavost.

The 2013/2014 season was concluded again by an open-air concert, this time at Hradčanské náměstí.

The summer between Bělohlávek’s second and third season with the Czech Philharmonic was spent relaxing as well as performing at summer festivals. In August and September, they went together on four tours to European countries, altogether giving twelve concerts in Austria, Great Britain, Germany, Switzerland, Italy and Slovakia. The Czech Philharmonic presented their new recording of Dvořák on these tours. For that reason, they performed with the cellist Alisa Weilerstein in several of the concerts, one of which took place on 24 August 2014 at the BBC Proms.

Last night it was the turn of a familiar, gilded ensemble from Old Europe, the Czech Philharmonic. There was a difference, to be sure, but it didn’t lie in technical virtuosity. That’s a given everywhere nowadays, with such a thriving international market in high-level orchestral training. It was something very subtle: a feeling of great power without aggression, exactitude without pedantically sharp edges, and a weight and clarity in the wind and brass. I’m vague as to the whereabouts of ‘Middle Europe’ on the map, but when I hear the Czech Philharmonic’s horns, I know I’m there.

Včera večer přišel na řadu již známý a uznávaný soubor ze Staré Evropy, Česká filharmonie. A určitě si bylo možné povšimnout rozdílu, ten však netkvěl v technické virtuositě. Ta se dnes rozumí samo sebou všude, když existuje tak prosperující mezinárodní trh vysoce kvalifikované orchestrální průpravy. Šlo o něco hlubšího: pocit obrovské síly bez agrese, přesnosti bez pedantsky ostrých hran a hloubka a čistota v dechových sekcích. Střední Evropu na mapě nedokážu přesně najít, ale když slyším žestě České filharmonie, vím s jistotou, že jsem tam.

The third season brought again many innovations and important musical events. Most importantly, however, all the major points outlined in the conception regarding the reform of the institution were implemented with unexpected speed. Hard work and a clear qualitative shift meant the orchestra became more sought-after by audiences, promoters and partners. And their support in turn enabled the orchestra to make bolder and more demanding plans.

One of the innovations of the 119th season were satellite broadcasts from the Rudolfinum to cinemas in October and December. In October, they broadcast Dvořák’s New World Symphony and other pieces and in December Jakub Jan Ryba’s Czech Christmas Mass. Both concerts were conducted by Bělohlávek.

In the cinema, the visual and audio experience has a high level of authenticity, we are therefore going to play aware of the fact that an unusually large number of concentrated and ardent listeners are out there with us, and that is what I am really looking forward to.

In November 2014, the Czech Philharmonic returned to the US after six years. On a tour that lasted almost three weeks, Bělohlávek, the French pianist Jean-Yves Thibaudet and the Philharmonic gave eleven concerts on the West and East coasts of the United States.

The highlight of the tour was on 16 November at the Carnegie Hall in New York. In front of almost three thousand New Yorkers, they played Dvořák’s Ninth, Janáček’s Taras Bulba and, together with Thibaudet, Liszt’s Piano Concerto No.2. Besides the concert, a special official ceremony took place at the Carnegie Hall on that day – Bělohlávek received the Antonín Dvořák Prize for his lifetime achievement. The following day, the Philharmonic performed in the Washington National Cathedral at a ceremonial concert commemorating twenty-five years from the Velvet Revolution and the third anniversary of Václav Havel’s passing.

…the performance of Dvorak’s “New World” Symphony that concluded the program was lovely, flexible in its tempos and phrasing. The strings were warm and caressing, the brasses brash and incisive; the woodwinds sang with a slightly nasal, Slavic character and danced with a playful show of elbows and knees.

Provedení Dvořákovy Novosvětské, které uzavřelo program večera, bylo krásné s pohotovými změnami tempa a frázování. Smyčce hrály s laskavou vroucností, žestě odvážně a břitce, zpěv dřevěných dechů měl slovanský, poněkud nazální zvuk. (...) S obdobnou samozřejmostí se tito interpreti chopili i blyštivě barevného Tarase Bulby. (…) Něžná místa nebyla o nic méně působivá než ta bouřlivá.

The choice of Dvořák’s Ninth to headline the Czech Philharmonic’s program seemed an obvious one.(…) Yet after hearing this performance, it’s hard to fault the musicians for wanting to show off. This was almost the Platonic Ideal of a Dvořák Ninth. It was an Ideal also in the sense that, hearing this symphony as it was played on Sunday, one got the sense that this is precisely what the music needs to sound like—in terms of texture, size, tone, and the rest. (…) Bělohlávek led the scherzo at a deliberate pace, but even at a moderate tempo, managed to sustain the music’s energy. As the opening raindrops evolved into a torrent, he remained a picture of physical economy. His arm gestures are minute, his body almost still. In fact, you hardly notice him, which is refreshing in an era of theatrical conducting.

Volba Dvořákovy Novosvětské za titulní skladbu koncertu se může zdát až příliš samozřejmá. (…) Nicméně po vyslechnutí tohoto provedení bychom jen těžko mohli hudebníky vinit z toho, že se chtěli pouze předvádět. Byl to téměř platonický ideál Dvořákovy deváté. Ideál to byl také v tom smyslu, že při poslechu provedení, kterého jsme byli svědky v neděli, se člověk neubránil pocitu, že přesně takto má tato hudba znít – ve smyslu textury, dynamiky, tónu a dalších. (…) Scherzo Bělohlávek řídil v úmyslně mírnějším tempu, ale i tak dokázal udržet energii. Jak se úvodní kapky rozmáhaly do obrovského proudu, dirigent zůstával obrazem fyzické hospodárnosti. Gesta jeho rukou jsou drobná, jeho tělo téměř nehybné. Vlastně si ho skoro nevšimnete, což je osvěžující v éře teatrálního dirigování.

In December, Bělohlávek conducted a concert performance of Bohuslav Martinů’s opera What Men Live By, following up on his interest in promoting this way of presenting opera. On 17, 18 and 19 December, the audience at the Rudolfinum could hear the Czech premiere of a work based on a story by L. N. Tolstoy that Martinů composed in the early 1950s while he was in the USA. A historically first recording of the opera was made at the concerts and released by Supraphon in 2018 together with Martinů’s First Symphony.

Jiří Bělohlávek presented the opera What Men Live By (whose theme is helping our neighbour and therefore showing how to live by the Gospel) as a charming, both in respect to music and ideas, pastoral, dear, beautiful and utterly positive work, one may even say joyful. He chose to collaborate with Vasilek’s chamber choir Martinů Voices and several soloists including Ivan Kusnjer in the main role. The performance had parameters of musical perfection and style – not only in the case of Kusnjer, but also of Jan Martiník and Jaroslav Březina. Lucie Silkenová and Ester Pavlů sang also, as well as other soloists from the choir. And there were two more important roles on the stage – Lukáš Mareček in a boy’s role and in the role of the narrator Josef Špaček, the orchestra’s concertmaster who could make a good use of his knowledge of English that he acquired while studying in the USA.

From the point of dramaturgy, the year 2015 was devoted to major vocal-instrumental works. In the first half of the year, Bělohlávek took the Czech Philharmonic on a tour to Spain, where they had five concerts. In March, they were resident artists at Vienna’s Musikverein – the three concerts there offered solely Czech programme: Martinů, Janáček, Suk and Dvořák. At the end of March they performed in three Polish cities: Warsaw, Katowice and Krakow.

The conductor and the orchestra quite naturally showed the musical roots of the articulated bitter idiom born out of romantic worlds of expression, while at the same time managing to smooth out the unevenness and jagged edges and transposing Janáček’s “speech melodies” into modernist rawness with a nice mix of earthy vehemence, brilliance and elegant vigour.

Dirigent a orchestr zcela přirozeně ukázali hudební kořeny zřetelně artikulovaného trpkého idiomu zrozeného z romantických výrazových světů, zároveň dokázali vyhrotit nevyrovnanost a rozeklané hrany a Janáčkovu „nápěvkovou mluvu“ nechali se skvělou směsí zemité prudkosti, brilance a elegantního elánu přejít v modernistickou syrovost.

The principal guest conductor of the Czech Philharmonic Manfred Honeck presented Walter Braunfels’ Te Deum at the Rudolfinum. During the season, Bělohlávek focused on the work of Gustav Mahler. At subscription concerts in April 2015, he conducted Mahler’s Symphony No. 2 in C minor, Resurrection, and on 22 May 2015 at the Prague Spring Festival, his Symphony No. 3 in D minor with Elisabeth Kulman (mezzosoprano), the Prague Philharmonic Choir and the Prague Philharmonic Children’s Choir. Further, they performed Dvořák’s Requiem in B-flat minor in June 2015 at the Smetanova Litomyšl Festival. On 27 June, they presented Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis at the German festival Kissinger Sommer (Bad Kissingen).

The April tour of Great Britain was also very successful, offering seven concerts in Leeds, Edinburgh, Nottingham, Bristol, Basingstoke, Birmingham and Saffron Walden. Dvořák’s Slavonic Dances and Seventh Symphony, Smetana’s Overture to The Bartered Bride, R. Vaughan-Williams’ The Lark Ascending and the violin concertos of Max Bruch and Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy performed by Josef Špaček and Chloë Hanslip were on the programme. In Birmingham, they played Mahler’s Symphony No. 2.

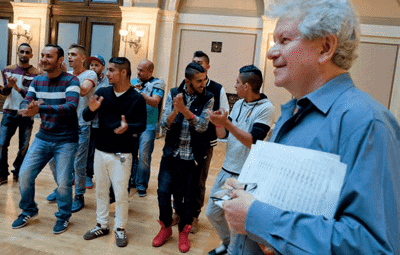

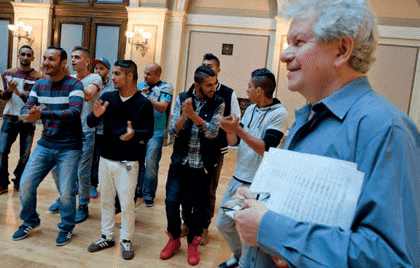

And again, the 119th season was ended by an open-air concert on 17 June 2015 with Bělohlávek conducting and Marek Eben presenting the programme which consisted also of Roma songs performed by Čhavorenge, a choir of Roma children led by Ida Kelarová. This concert highlighted the collaboration between the Czech Philharmonic and Ida Kelarová that had been developed already in the previous seasons (and has continued intensively until today).

Maestro Bělohlávek! … I was so nervous before meeting him for the first time. Of course, I esteem him highly as a professional, but I was saying to myself – what would he be like as a person? But the moment I sat down on the sofa in his office and he spoke, I felt relaxed. His voice is beautiful, his tone balanced, and I could hear in it his genuine interest – he appealed to me deeply. The same was true for the kids – they asked him many questions and they were fantastically disciplined during the rehearsal. They understood who was standing before them and they knew how rare it is when the Czech Philharmonic’s chief conductor works with Roma children from Eastern Slovakian villages.

In June 2015, the collaboration of the Czech Philharmonic and the Association of Elementary Art Schools had its climax in a final concert in the Dvořák Hall of the Rudolfinum. From the autumn of 2014, eighty-five pupils of elementary music schools from five regions of the Czech Republic had been preparing for this concert of 21 June with their teachers and the conductor Ladislav Cigler. The orchestra consisting of members of the Philharmonic and these young musicians performed Dvořák’s Symphony No. 8 under Bělohlávek’s baton and Smetana’s Šárka under Ladislav Cigler.

After the summer holiday, the 120th jubilee season began. No special soloist was asked to open the season, it was decided that the spotlight should shine on the orchestra itself. The programme therefore included only symphonic works. On 1 and 2 October 2015, Bělohlávek conducted Janáček’s symphonic ballad Šumařovo dítě (A Fiddler's Child), Suk’s Fairy Tale and Dvořák’s Slavonic Dances op. 72.

The highlight of the Czech Philharmonic’s tour activities in 2015 was the Japanese tour of October and November. Conducted by Bělohlávek, they played eight concerts there - three in Tokyo and one in Toyama, Fukuoka, Nagoya, Hamamatsu and Yokohama. In Tokyo, they performed at the two most prestigious halls – Suntory Hall and NHK Hall. The concerts included Smetana’s Má vlast, Dvořák’s Symphony No. 9 in E minor, Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 5 in E minor, Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 in C minor and two instrumental concertos – Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto in E minor performed by Sayaka Shoji and Rachmaninov’s Piano Concerto No. 2 in C minor, performed by Daniil Trifonov.

At the end of the year, Bělohlávek looked back at his collaboration with the Czech Philharmonic up to then in an in-depth interview for the magazine Forbes. Refreshing the creative spirit in the orchestra was what he saw as the most important achievement.

What I consider the highest achievement is that we managed to revive the orchestra’s creative spirit. When I say this, it sounds like a cliché, however, this aspect is of utmost importance in artistic ensembles. Sometimes we see ensembles that play perfect technique but bring no interesting music, it may be only mechanic drill. Technical refinement is of course one of the fundamental qualities of a first-class ensemble but it is not self-redemptive. What distinguishes an excellent orchestra from a good one is exactly this level of inspired creativity.

Events of the jubilee season culminated in early 2016. 4 January marked the 120th anniversary of the first public concert of the Czech Philharmonic when Antonín Dvořák himself stood in front of the orchestra and conducted a programme of his own works. The chief conductor Bělohlávek prepared an almost identical programme, the only difference being that The Slavonic Rhapsody No. 3 was left out. There was then enough space to perform the complete Biblical Songs, of which only five had been orchestrated in 1896. The solo part was sung by Jan Martiník, a soloist of the Staatsoper Berlin. The concert overture Othello and Symphony No.9 in E minor completed the programme.

Following the first calm, majestic tones, the passionate symbolism of the concert overture Othello, op. 93 set the music on fire thanks to Jiří Bělohlávek who was overflowing with energy and thanks to the wonderfully playing orchestra - it became clear that the evening would be unforgettable. However, thanks to the bass Jan Martiník, Othello was surpassed by the Biblical Songs, op. 99 (…) The New World Symphony, op. 95 seemed another story altogether. Fluffy, energetic, precise, dancelike (Scherzo), balanced in tempos from the very first tones … The conductor cherished every phrase, every musical molecule, through the players of the Philharmonic. It was such an impressive performance that it occurred to me that I was witnessing a better performance than had been recorded by Decca a few years earlier for the Dvořák set. The orchestra playing with all enthusiasm did a great job.

24 February 2016 marked another important jubilee - Jiří Bělohlávek celebrated his seventieth birthday. A number of articles evaluating Bělohlávek’s career appeared in the media and the radio and television released many programmes using archive material and recordings where Bělohlávek was an important protagonist. Marking this jubilee, the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague awarded him an honourable degree.

The orchestra, friends from artistic circles, collaborators and other personalities wished Jiří Bělohlávek a happy birthday on Saturday 13 February, when they gathered at the Rudolfinum for his birthday concert. Bělohlávek’s former student Jakub Hrůša conducted the orchestra in the first half of the concert, in the second part of the concert the birthday-boy himself took over the baton. Sopranos Karita Mattila and Hibla Gerzmawa, tenor Jaroslav Březina, bass-baritone Adam Plachetka, bass Jan Martiník and Richard Novák, pianist Paul Lewis, violinist Josef Špaček and cellist Václav Petr added to the graceful atmosphere of the evening with their solo performances. And a big surprise came in the form of an enormous cake decorated by little figures of all players and the chief conductor which was created by the French horn player Kateřina Javůrková with her confectionery team. Thanks to the total number of 123 figures, this cake entered the Czech Book of Records.

In April, the Czech Philharmonic and Bělohlávek prepared another concert performance of an opera - Janáček’s Jenůfa. The chief conductor invited soloists Karita Mattila (Kostelnička), Adriana Kohútková (Jenůfa), Jaroslav Březina (Števa), Aleš Briscein (Laco) and others and the Czech Philharmonic Choir of Brno. The opera was performed in Prague on 15 April and then the entire ensemble moved to London, where they presented Janáček’s work on 18 April at the Southbank Centre.

The whole evening, though, was revelatory. Bělohlávek’s lyrical way with Janáček speaks volumes in a work in which love and pain are in constant proximity, and the Czech Philharmonic’s playing, richly detailed and superbly focused, was incomparable. The cast sang with a beauty of line that made other performances of the work seem overly declamatory. Adriana Kohútková is among the finest of Jenůfas, hauntingly vulnerable, the voice itself exquisite. Aleš Briscein made a well-nigh ideal Laca – passionate, grieving, powerfully self-aware. Jaroslav Březina’s arrogant, brutally sensual Steva was equally outstanding.

Celý večer byl nabitý sděleními. Bělohlávkův lyrický přístup k Janáčkovi nám dává pochopit tolik z tohoto díla, v němž láska a bolest jsou v nepřetržité blízkosti, a hra České filharmonie byla bohatá na detaily, úžasně soustředěná a tedy naprosto nesrovnatelná. Sólisté zpívali s krásnou linií, v jejímž světle působí všechna ostatní provedení této opery až moc deklamačně. Adriana Kohútková je jednou z nejlepších Jenůf, děsivě zranitelná, s mimořádným hlasem. Aleš Briscein vytvořil téměř ideálního Lacu – vášnivého, truchlícího, silně sebezpytujícího. Jaroslav Březina ztvárnil arogantního, brutálně smyslného Števu také výjimečně.

The following months were devoted to opera as well. In June 2016, Bělohlávek conducted Jenůfa at the Opera San Francisco. The Swedish soprano Malin Byström performed the role of Jenůfa and Karita Mattila was Kostelnička. The rehearsals and Bělohlávek’s stay in San Francisco are described in Bělohlávek’s diary. Two months later on 19 August 2016, Bělohlávek presented a concert performance of The Makropulos Affair with the BBC Symphony Orchestra, Karita Mattila and Czech soloists at the BBC Proms.

The 121st season was opened by concerts on 29 and 30 September 2016 featuring Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto in D major with Joshua Bell and Mahler’s Song of the Earth with Bernarda Fink (mezzo-soprano) and Pavel Černoch (tenor). Not only did the musical qualities draw the attention of the audience but also the striking change in the conductor’s appearance who lost his legendary white hair and a lot of weight due to cancer treatment.

Bělohlávek did not talk of his illness publicly. When asked, he would not avoid answering, but otherwise he considered it his private matter. He had been fighting the illness bravely since he took up the position of the chief conductor in 2012. The orchestra, friends and close colleagues knew of the diagnosis, but an uninformed eye would not have recognized anything in the early years of his illness. As he would say, music was the best cure for him. The elegance and energy with which he handled everything was admired by the presenter Marek Eben, who collaborated with him on education programmes: “He was an immensely courageous man. The way he managed to deal with his illness was impressive. When he stood in front of the orchestra, you would recognize absolutely nothing, his energy and commitment were those of a healthy man.” [ 30 ]

The director Roman Vávra, who was making a film with Bělohlávek for the last two years, also spoke of his approach to the illness.

He was absolutely disarming in this. He said that he did not understand the illness as his opponent but as a challenge and inspiration of a kind. For instance, I heard Magdalena Kožená speaking about how even international orchestras that Jiří Bělohlávek conducted towards the close of his life, started to play suddenly in a different way, about how the whole ensemble, without any explanation, understood the fragility and vulnerability of his condition and at the same time the amazing inner strength of the conductor – and musical miracles were born in this way. I cannot describe it well; I don’t understand it. These are situations that have nothing to do with reason and experience, they happen deep in us and above us.

In the second half of 2016, the Czech Philharmonic went on two important tours. In October, they toured China giving eight concerts under Bělohlávek’s baton. Next to popular works by Antonín Dvořák, Bedřich Smetana and Leoš Janáček, the concerts featured compositions by lesser-known Czech composers - Bohuslav Martinů, Josef Suk, Zdeněk Fibich and Oskar Nedbal. At the turn of November and December, they gave six concerts in Germany.

In addition to the traditional New Year’s Concert on 1 January, one more important event took place, when Bělohlávek, in the Presidential lounge, signed the contract for further six years. He was to stay in the position of chief conductor and music director until the 2021/2022 season. Due to their mutually friendly relations with the management, he had been conducting the Philharmonic without a contract since the beginning of the 121st season. In an interview for DVTV, he presented the plans he had with the orchestra for the following years and confessed that what he was experiencing with the Czech Philharmonic was the most beautiful time of his entire professional life.

It is the best that I have experienced with the Czech Philharmonic. And it falls into the highest category that I have ever experienced in my entire career. And I am happy that it is here, at home. And that it is with this orchestra because it is the closest to my heart. The ensemble that I grew up with as Václav Neumann’s assistant. I was breast-fed by the sound of the Czech Philharmonic, and I’ve got it still under my skin firmly.

Bělohlávek had two recording projects in the first half of 2017. A live recording of Martinů’s Symphony No. 4, Strauss’ Concerto for French Horn No. 2 with the soloist Radek Baborák and Janáček’s Sinfonietta was made at subscription concerts in February. The recording of Martinů’s work was part of a co-production project of the Czech Philharmonic, Czech TV and German TV company UNITEL which made audio-visual recordings of all of Martinů’s symphonic works. And another project took place in February – the recording of Dvořák’s Biblical Songs with Jan Martiník (bass) for the DECCA label as part of a set of Dvořák’s spiritual compositions.

At the beginning of May, Bělohlávek and the Czech Philharmonic performed Mahler’s Symphony No. 5 in C sharp minor and Mozart’s Fifth Violin Concerto with Nikolaj Znaider. The audience’s reaction to the performance of Mahler’s work was immensely positive and the Czech Philharmonic was later awarded the Classic Prague Awards 2017 in the orchestral category for it. On Sunday 7 May, Bělohlávek conducted the PKF - Prague Philharmonia in the opening concert of the twentieth Martinů Fest. It was his very last concert.

The first day of June brought very sad news – Jiří Bělohlávek passed away in the evening of 31 May. Although people knew that he was fighting a serious illness and that he had suggested to the organizers of the Prague Spring Festival that Petr Altrichter should take over his festival performances, nobody expected that it would be so sudden.

Jiří Bělohlávek was part of the family, and it is very personal for all of us. Everybody knew that he was ill and that one day he would die of this illness, but everybody hoped that it would come much much later. He himself had plans for 2019 and 2020.

With Jiří Bělohlávek’s passing, a world-class conductor, a tireless promoter of Czech music and an exceptional person of high artistic and human qualities left us. After he joined the Czech Philharmonic in 2012, the orchestra had a lot of exceptionally successful performances and regained a respected position at home and abroad.

Main sources

- 1.

Bělohlávek: Umělec musí být stále nespokojen, právě ta cesta, hledání dokonalosti, to je ten smysl. DVTV 2017 (17. 1.) Available online.

- 2.

KLEPAL, Boris: Bez spokojeného orchestru to nejde. Deset let s Českou filharmonií. Magazín České filharmonie. 2020, č. 4 (17. 9.) Available online

- 3.

MAREČEK, David: Vzpomínka na Jiřího Bělohlávka. Hudební rozhledy 2017. Available online

- 4.

JAROLÍMKOVÁ, Hana: S Jiřím Bělohlávkem (nejen) o České filharmonii. Hudební rozhledy 2012, č. 9, s. 3.

- 5.

DRÁPELOVÁ, Věra: Chci orchestr pořádně nažhavit. MF Dnes 2012 (Pražské vydání), č. 230, s. 5.

- 6.

KALIVODOVÁ, Kateřina: Jiří Bělohlávek: Dirigent obhajuje svoji autoritu dnes a denně. TopVip.cz 2012, 23. 6. Available online

- 7.

VEBER, Petr; STEHLÍK, Luboš: Jiří Bělohlávek – perfekcionista, pro něhož není dokonalost cílem, ale začátkem. Harmonie 2012, 9. 10.

- 8.

TUREK, Pavel: Budování orchestru. S generálním ředitelem České filharmonie Davidem Marečkem. Respekt 2017, č. 24, s. 46.

- 9.

ŘÍHA, Vladimír: Třikrát Česká filharmonie. Hudební rozhledy 2012. Available online

- 10.

KADLEC, Petr: Bělohlávek a Česká filharmonie našli společnou řeč. Aktuálně.cz 2012 (8. 10.). Available online

- 11.

VEBER, Petr; STEHLÍK, Luboš: Jiří Bělohlávek – perfekcionista, pro něhož není dokonalost cílem, ale začátkem. Harmonie 2012 (9. 10.). Available online

- 12.

EVANS, Rian: Czech Philharmonic Orchestra/Bělohlávek – review (St David's Hall, Cardiff). The Guardian 2013, 18. 4.

- 13.

Ozvěny ze Smetanovy Litomyšle. Hudební rozhledy 2013, č. 8, s. 15–16. Available online

- 14.

VAŠATOVÁ, Jana: Telefonotéka. Český rozhlas Vltava 2013 (6. 10.). Available online

- 15.

LAPHAY, Pierre-Emmanuel: La Dame de Pique – Zurich. Forumopera.com 2014, 11. 4. Available online

- 16.

https://www.ceskatelevize.cz/porady/10896744607-ceska-filharmonie-open-air-koncert-2014/21454215916/

- 17.

MAŇOUROVÁ, Lucie: „Bylo to velmi příjemné odpoledne“ aneb jak Česká filharmonie neveřejně nastudovala dvě soutěžní skladby. Magazín České filharmonie 2016 (21. 1.). Dostupné online

- 18.

VEBER, Petr: Bělohlávkova Má vlast. Harmonie 2014 (18. 5.). Available online

- 19.

CLEMENTS, Andrew: Czech PO/Bělohlávek: Smetana's Má Vlast - a worthy tribute to a fine musician. The Guardian 2018 (18. 1.). Available online

- 20.

HEWETT, Ivan: BBC Prom 50, Czech Philharmonic, review: 'very subtle'. The Telegraph 2014 (25. 8.). Available online

- 21.

DVOŘÁK, Vít: Česká filharmonie s Bělohlávkem poprvé v přímém přenosu do kin. Opera Plus 2014 (25. 10.). Available online

- 22.

OESTREICH, James R. Regardless of Offstage Worries, Onstage It’s All Artistry. The New York Times 2014 (17. 11.). Available online

- 23.

SIMPSON, Eric. C.: Home dishes prove ideal menu for Czech Philharmonic. New York Classical Review 2014 (17. 11.). Available online

- 24.

VEBER, Petr: Čím lidé žijí. Harmonie 2014 (29. 12.). Available online

- 25.

ENDER, Daniel: Wucht und Tränendrüsentröpfchen. Schmelz und Kraft: Die Tschechische Philharmonie gastierte im Wiener Musikverein. Der Standard 2015 (20. 3.). Dostupné online

- 26.

Setkání s Jiřím Bělohlávkem. Romano drom 2015. Available online

- 27.

ŠIMŮNEK, Petr: Jiří Bělohlávek: Dirigent může orchestr nadchnout, ale i otrávit. Forbes 2016, č. 1. Available online

- 28.

STEHLÍK, Luboš: Díky, Antoníne Dvořáku. Harmonie 2016, č. 2, s. 49.

- 29.

ASHLEY, Tim: Jenůfa review – formidable Mattila is devastating as the Kostelnička. The Guardian 2016 (19. 4.). Available online

- 30.

SLÍVOVÁ, Hana: Zemřel světový dirigent Jiří Bělohlávek. Jeho službu hudbě ocenila i královna Alžběta II. Aktuálně.cz 2017 (1. 6.) Available online

- 31.

ČÍŽEK, Ondřej: Křehkost, která tvoří zázraky: Rozhovor s dokumentaristou Romanem Vávrou o Jiřím Bělohlávkovi. Magazín České filharmonie 2019 (1. 11.). Available online

- 32.

DRTINOVÁ, Daniela: Bělohlávek: Umělec musí být stále nespokojen, právě ta cesta, hledání dokonalosti, to je ten smysl. DVTV 2017. (11. 1.) Available online

- 33.

TUREK, Pavel: Budování orchestru. S generálním ředitelem České filharmonie Davidem Marečkem. Respekt 2017, č. 24, s. 48.

Bělohlávek: Umělec musí být stále nespokojen, právě ta cesta, hledání dokonalosti, to je ten smysl. DVTV 2017 (17. 1.) Available online.

KLEPAL, Boris: Bez spokojeného orchestru to nejde. Deset let s Českou filharmonií. Magazín České filharmonie. 2020, č. 4 (17. 9.) Available online

MAREČEK, David: Vzpomínka na Jiřího Bělohlávka. Hudební rozhledy 2017. Available online

JAROLÍMKOVÁ, Hana: S Jiřím Bělohlávkem (nejen) o České filharmonii. Hudební rozhledy 2012, č. 9, s. 3.

DRÁPELOVÁ, Věra: Chci orchestr pořádně nažhavit. MF Dnes 2012 (Pražské vydání), č. 230, s. 5.

KALIVODOVÁ, Kateřina: Jiří Bělohlávek: Dirigent obhajuje svoji autoritu dnes a denně. TopVip.cz 2012, 23. 6. Available online

VEBER, Petr; STEHLÍK, Luboš: Jiří Bělohlávek – perfekcionista, pro něhož není dokonalost cílem, ale začátkem. Harmonie 2012, 9. 10.

TUREK, Pavel: Budování orchestru. S generálním ředitelem České filharmonie Davidem Marečkem. Respekt 2017, č. 24, s. 46.

ŘÍHA, Vladimír: Třikrát Česká filharmonie. Hudební rozhledy 2012. Available online

KADLEC, Petr: Bělohlávek a Česká filharmonie našli společnou řeč. Aktuálně.cz 2012 (8. 10.). Available online

VEBER, Petr; STEHLÍK, Luboš: Jiří Bělohlávek – perfekcionista, pro něhož není dokonalost cílem, ale začátkem. Harmonie 2012 (9. 10.). Available online

EVANS, Rian: Czech Philharmonic Orchestra/Bělohlávek – review (St David's Hall, Cardiff). The Guardian 2013, 18. 4.

Ozvěny ze Smetanovy Litomyšle. Hudební rozhledy 2013, č. 8, s. 15–16. Available online

VAŠATOVÁ, Jana: Telefonotéka. Český rozhlas Vltava 2013 (6. 10.). Available online

LAPHAY, Pierre-Emmanuel: La Dame de Pique – Zurich. Forumopera.com 2014, 11. 4. Available online

https://www.ceskatelevize.cz/porady/10896744607-ceska-filharmonie-open-air-koncert-2014/21454215916/

MAŇOUROVÁ, Lucie: „Bylo to velmi příjemné odpoledne“ aneb jak Česká filharmonie neveřejně nastudovala dvě soutěžní skladby. Magazín České filharmonie 2016 (21. 1.). Dostupné online

VEBER, Petr: Bělohlávkova Má vlast. Harmonie 2014 (18. 5.). Available online

CLEMENTS, Andrew: Czech PO/Bělohlávek: Smetana's Má Vlast - a worthy tribute to a fine musician. The Guardian 2018 (18. 1.). Available online

HEWETT, Ivan: BBC Prom 50, Czech Philharmonic, review: 'very subtle'. The Telegraph 2014 (25. 8.). Available online

DVOŘÁK, Vít: Česká filharmonie s Bělohlávkem poprvé v přímém přenosu do kin. Opera Plus 2014 (25. 10.). Available online

OESTREICH, James R. Regardless of Offstage Worries, Onstage It’s All Artistry. The New York Times 2014 (17. 11.). Available online

SIMPSON, Eric. C.: Home dishes prove ideal menu for Czech Philharmonic. New York Classical Review 2014 (17. 11.). Available online

VEBER, Petr: Čím lidé žijí. Harmonie 2014 (29. 12.). Available online

ENDER, Daniel: Wucht und Tränendrüsentröpfchen. Schmelz und Kraft: Die Tschechische Philharmonie gastierte im Wiener Musikverein. Der Standard 2015 (20. 3.). Dostupné online

Setkání s Jiřím Bělohlávkem. Romano drom 2015. Available online

ŠIMŮNEK, Petr: Jiří Bělohlávek: Dirigent může orchestr nadchnout, ale i otrávit. Forbes 2016, č. 1. Available online

STEHLÍK, Luboš: Díky, Antoníne Dvořáku. Harmonie 2016, č. 2, s. 49.

ASHLEY, Tim: Jenůfa review – formidable Mattila is devastating as the Kostelnička. The Guardian 2016 (19. 4.). Available online

SLÍVOVÁ, Hana: Zemřel světový dirigent Jiří Bělohlávek. Jeho službu hudbě ocenila i královna Alžběta II. Aktuálně.cz 2017 (1. 6.) Available online

ČÍŽEK, Ondřej: Křehkost, která tvoří zázraky: Rozhovor s dokumentaristou Romanem Vávrou o Jiřím Bělohlávkovi. Magazín České filharmonie 2019 (1. 11.). Available online

DRTINOVÁ, Daniela: Bělohlávek: Umělec musí být stále nespokojen, právě ta cesta, hledání dokonalosti, to je ten smysl. DVTV 2017. (11. 1.) Available online

TUREK, Pavel: Budování orchestru. S generálním ředitelem České filharmonie Davidem Marečkem. Respekt 2017, č. 24, s. 48.